SQLModel User Guide

# Install SQLModel

Create a project directory, create a virtual environment, activate it, and then install SQLModel, for example with:

pip install sqlmodel

As SQLModel is built on top of SQLAlchemy and Pydantic, when you install sqlmodel they will also be automatically installed.

# Install DB Browser for SQLite

Remember that SQLite is a simple database in a single file.

For most of the tutorial I'll use SQLite for the examples.

Python has integrated support for SQLite, it is a single file read and processed from Python. And it doesn't need an External Database Server, so it will be perfect for learning.

In fact, SQLite is perfectly capable of handling quite big applications. At some point you might want to migrate to a server-based database like PostgreSQL(which is also free). But for now we'll stick to SQLite.

Though the tutorial I will show you SQL fragments, and Python examples. And I hope (and expect) you to actually run them, and verify that the database is working as expected and showing you the same data.

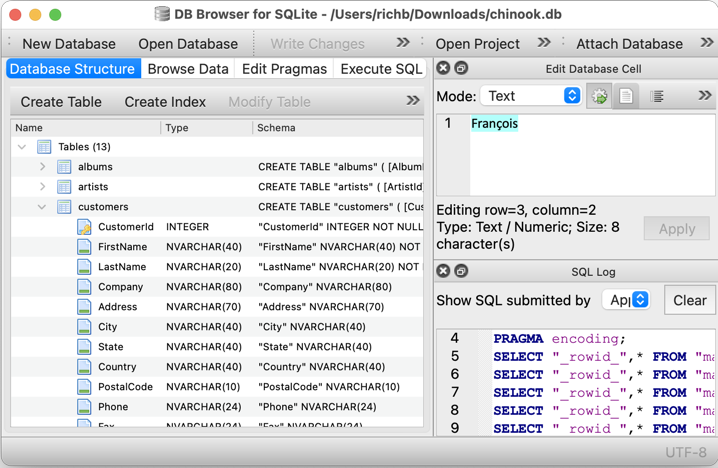

To be able to explore the SQLite file yourself, independent of Python code (and probably at the same time), I recommend you use DB Browser for SQLite.

It's a great and simple program to interact with SQLite database (SQLite files) in a nice user interface.

Go ahead and Install DB Browser for SQLite, it's free.

# Tutorial - User Guide

In this tutorial you will learn how to use SQLModel.

# Type hints

If you need a refresher about how to use Python type hints (type annotations), check FastAPI's Python types intro.

You can also check the mypy cheat sheet.

SQLModel uses type annotations for everything, this way you can use a familiar Python syntax and get all the editor support possible, with autocompletion and in-editor error checking.

# Intro

This tutorial shows you how to use SQLModel with all its features, step by step.

Each section gradually builds on the previous ones, but it's structured to separate topics, so that you can go directly to any specific one to solve your specific needs.

It is also built to work as a future reference.

So you can come back and see exactly what you need.

# Run the code

All the code blocks can be copied and used directly (they are tested Python files).

It is HIGHLY encouraged that you write or copy the code, edit it, and run it locally.

Using it in your editor is what really shows you the benefits of SQLModel, seeing how much code it saves you, and all the editor support you get, with autocompletion and in-editor error checks, preventing lots of bugs.

Running the examples is what will really help you understand what is going on.

You can learn a lot more by running some examples and playing around with them than by reading all the docs here.

# Create a Table with SQL

Let's get started!

We will:

- Create a SQLite database with DB Browser for SQLite.

- Create a table in the database with DB Browser for SQLite.

We'll add data later. For now, we'll create the database and the first table structure.

We will create a table to hold this data:

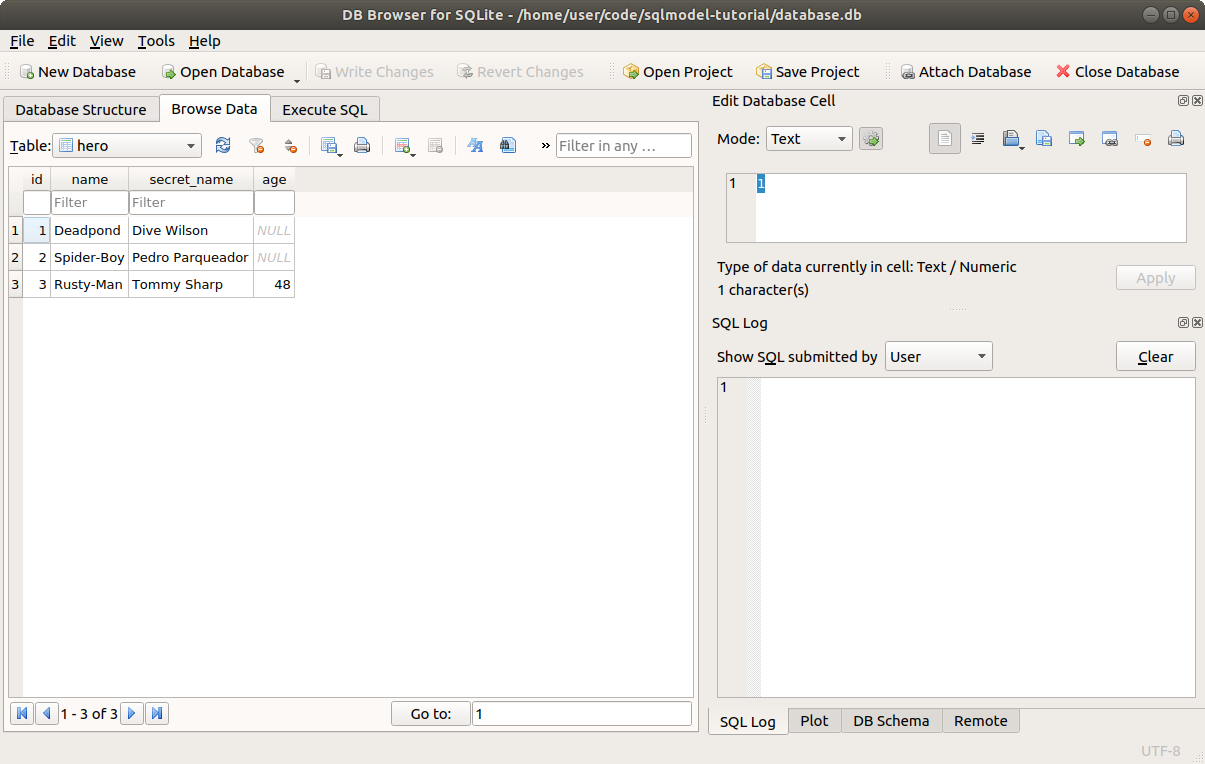

| id | name | secret_name | age |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Deadpond | Dive Wilson | null |

| 2 | Spider-Boy | Pedro Parqueador | null |

| 3 | Rusty-Man | Tommy Sharp | 48 |

# Create a Database

SQLModel and SQLAlchemy are based on SQL.

They are designed to help you with using SQL through Python classes and objects. But it's still always very useful to understand SQL.

So let's start with a simple, pure SQL example.

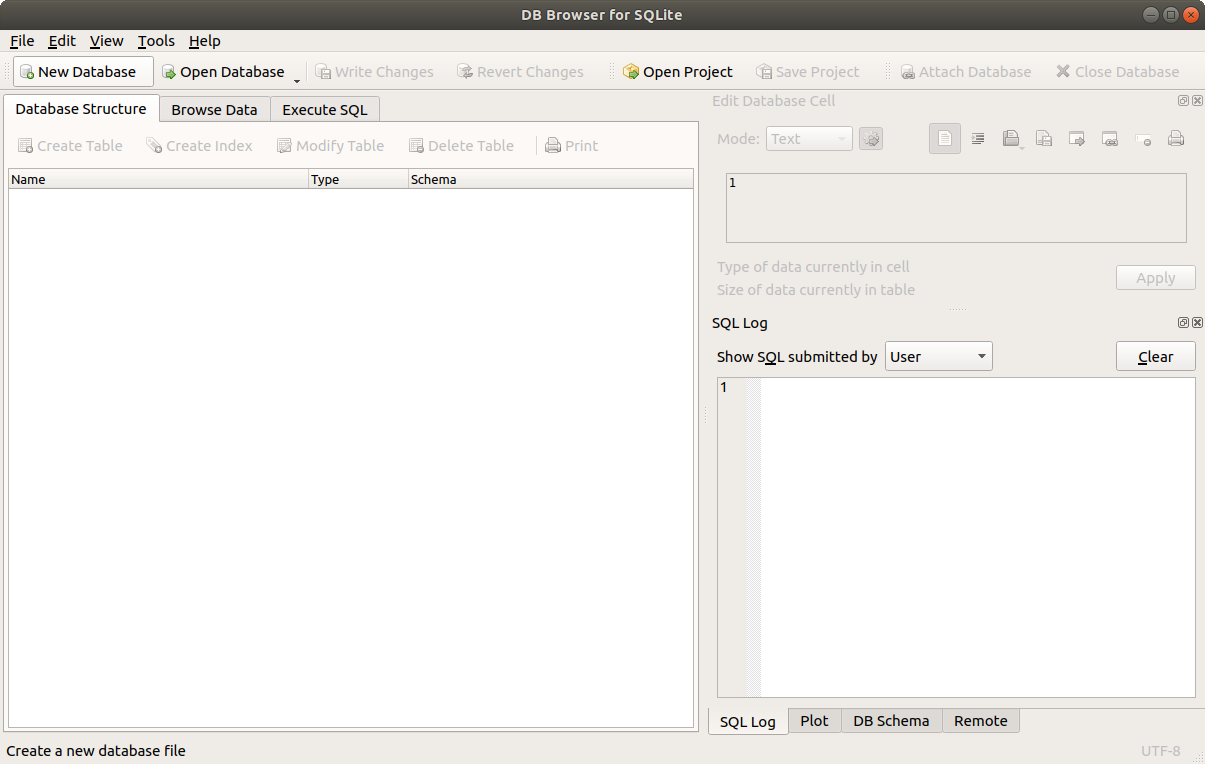

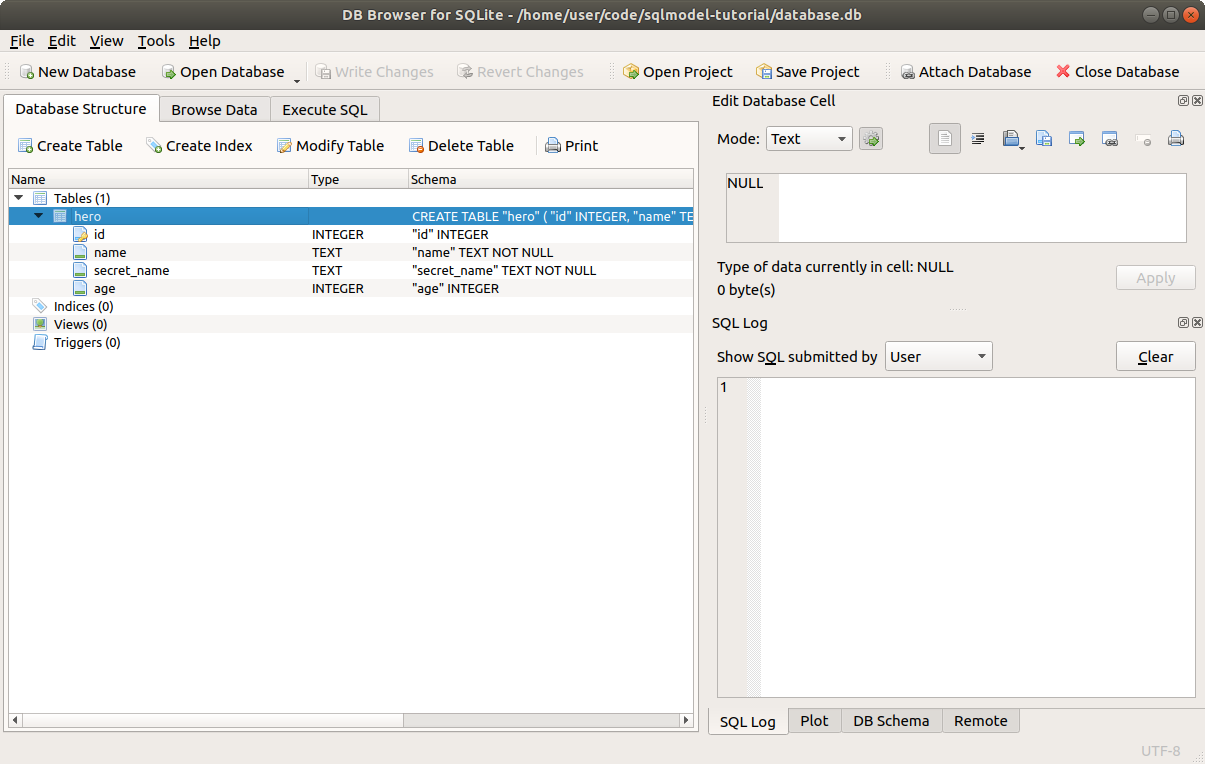

Open DB Browser for SQLite.

Click the button New Database:

A dialog should show up. Go to the project directory you created and save the file with a name of database.db.

It's common to save SQLite database files with an extension of .db. Sometimes also .sqlite.

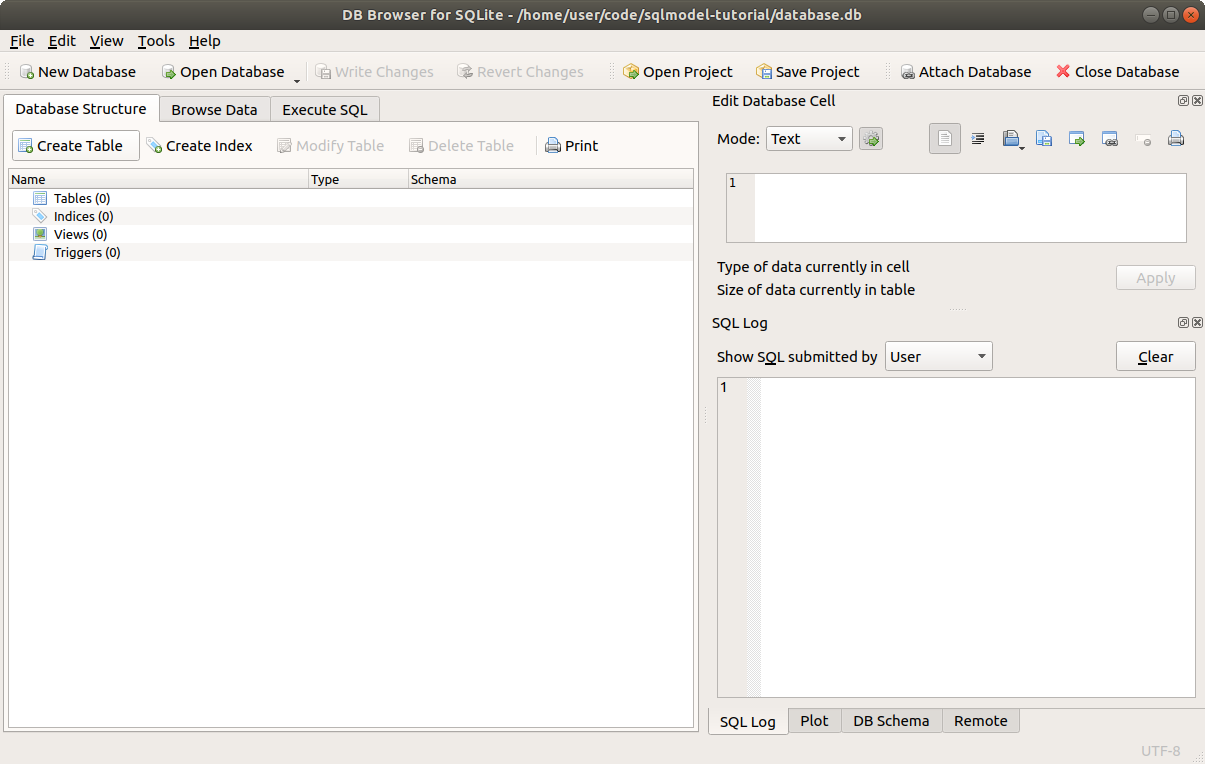

# Create a Table

After doing that, it might prompt you to create a new table right away.

If it doesn't, click the button Create Table.

Then you will see the dialog to create a new table.

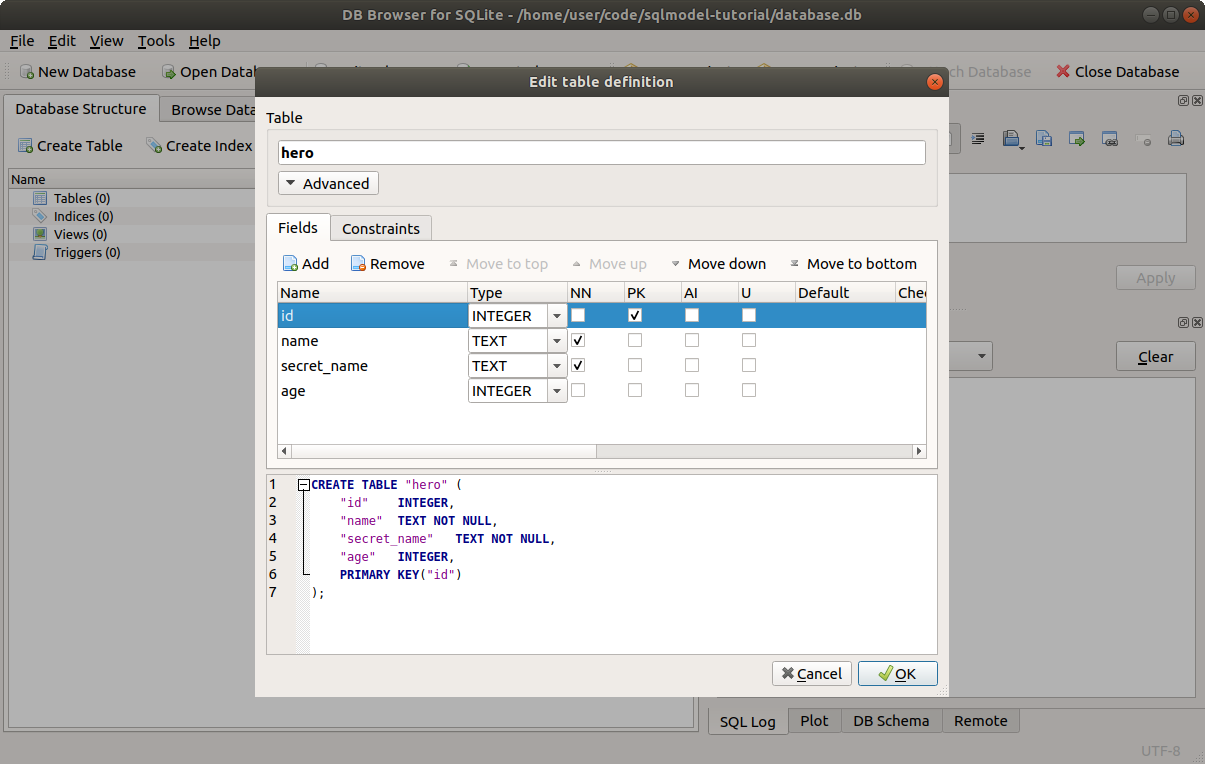

So, let's create a new table called hero with the following columns:

id: anINTEGERthat will be the primary key (checkPK).name: aTEXT, it should beNOT NULL(checkNN), so, it should always have a value.secret_name: aTEXT, it should beNOT NULLtoo (checkNN).age: anINTEGER, this one can beNULL, so you don't have to check anything else.

Click OK to create the table.

While you click on the Add button and add the information, it will create and update the SQL statement that is executed to create the table:

CREATE TABLE "hero" ( -- Create a table with the name hero. Also notice that the columns for this table are declared

-- inside the parenthesis "(" that starts here.

"id" INTEGER, -- The id column, an INTEGER. This is declared as the primary key at the end.

"name" TEXT NOT NULL, -- The name column, a TEXT, and it should always have a value NOT NULL.

"secret_name" TEXT NOT NULL, -- The secret_name column, another TEXT, also NOT NULL

"age" INTEGER, -- The age column, an INTEGER. This one doesn't have NOT NULL, so it can be NULL.

PRIMARY KEY("id") -- The PRIMARY KEY of all this is the id column.

); -- This is the end of the SQL table, with final parenthesis ")". It also has the semicolon ";" that marks the end of

-- the SQL statement. There could be more SQL statements in the same SQL string.

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

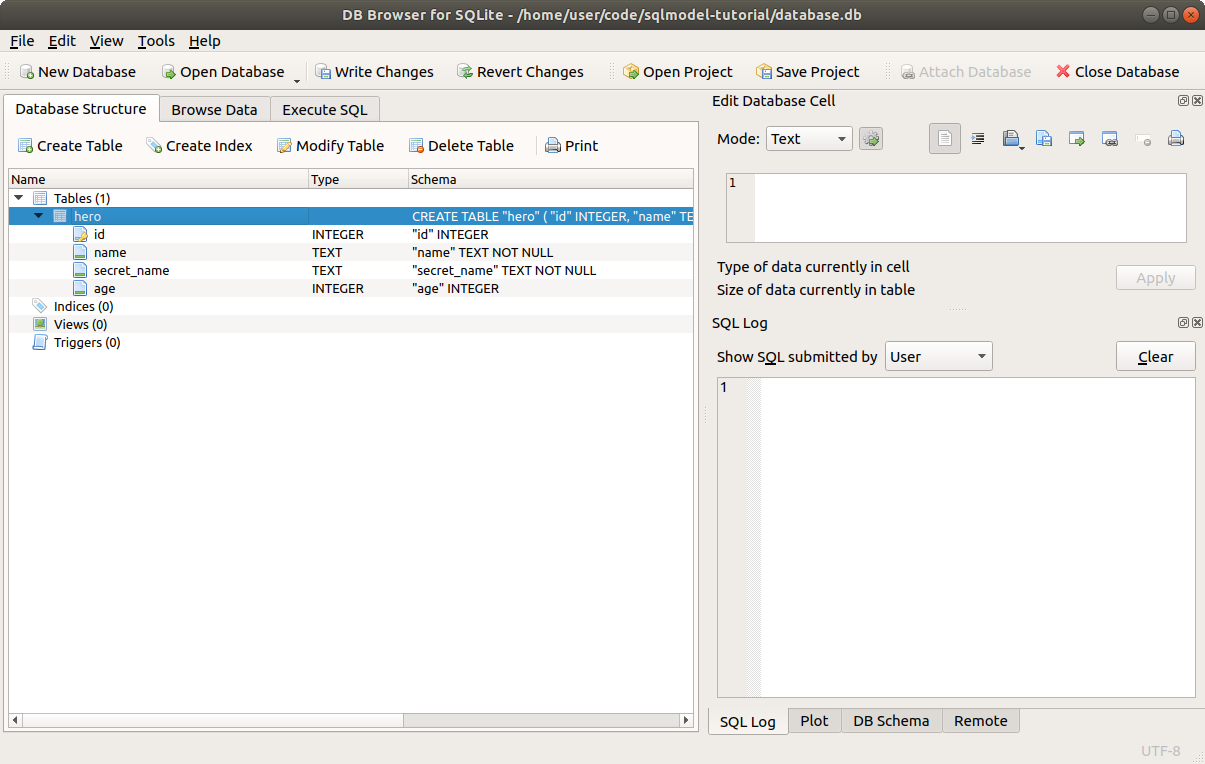

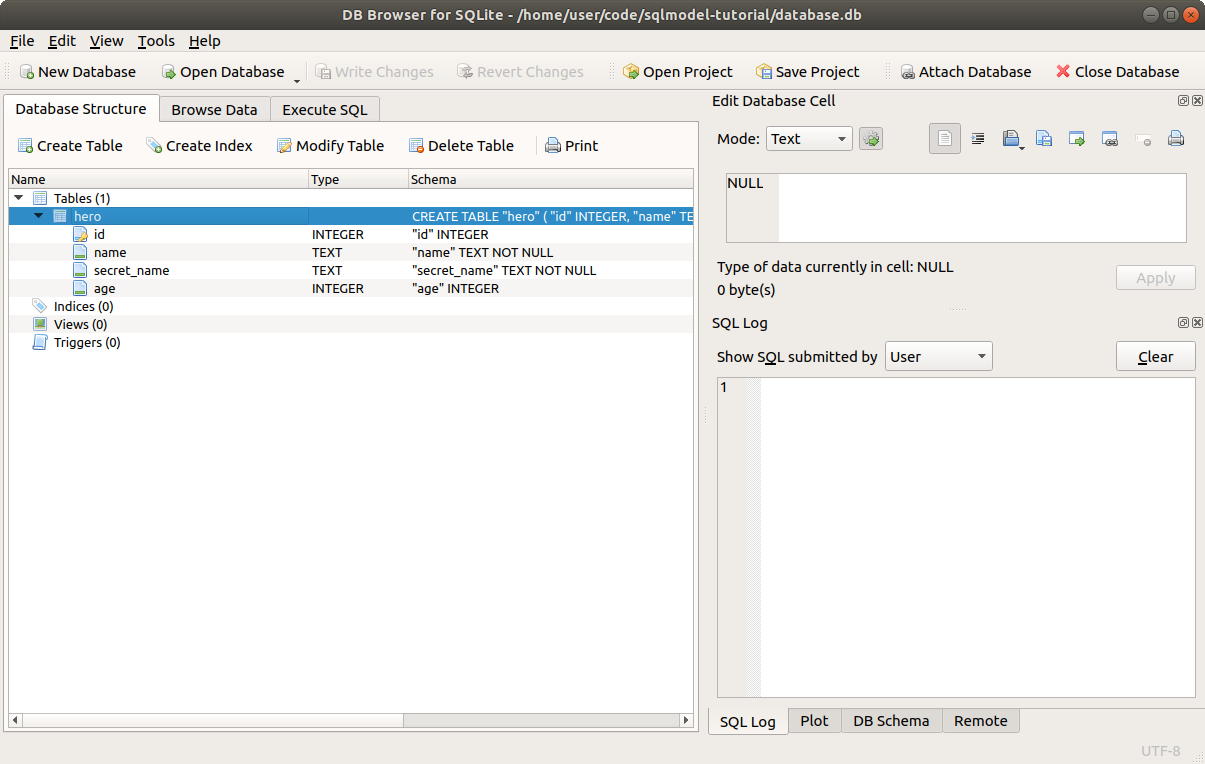

Now you will see that it shows up in the list of Tables with the columns we specified.

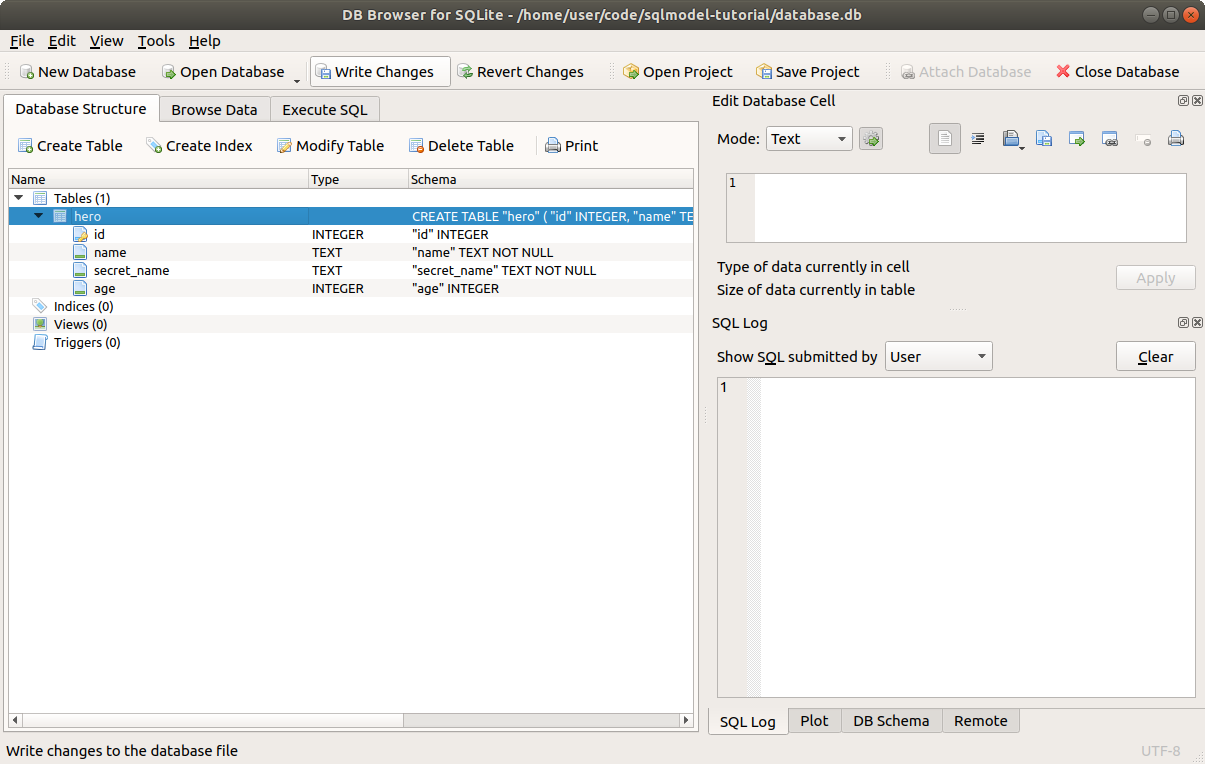

The only step left is to click Write Changes to save the changes to the file.

After that, the new table is saved in this database on the file ./database.db.

# Confirm the Table

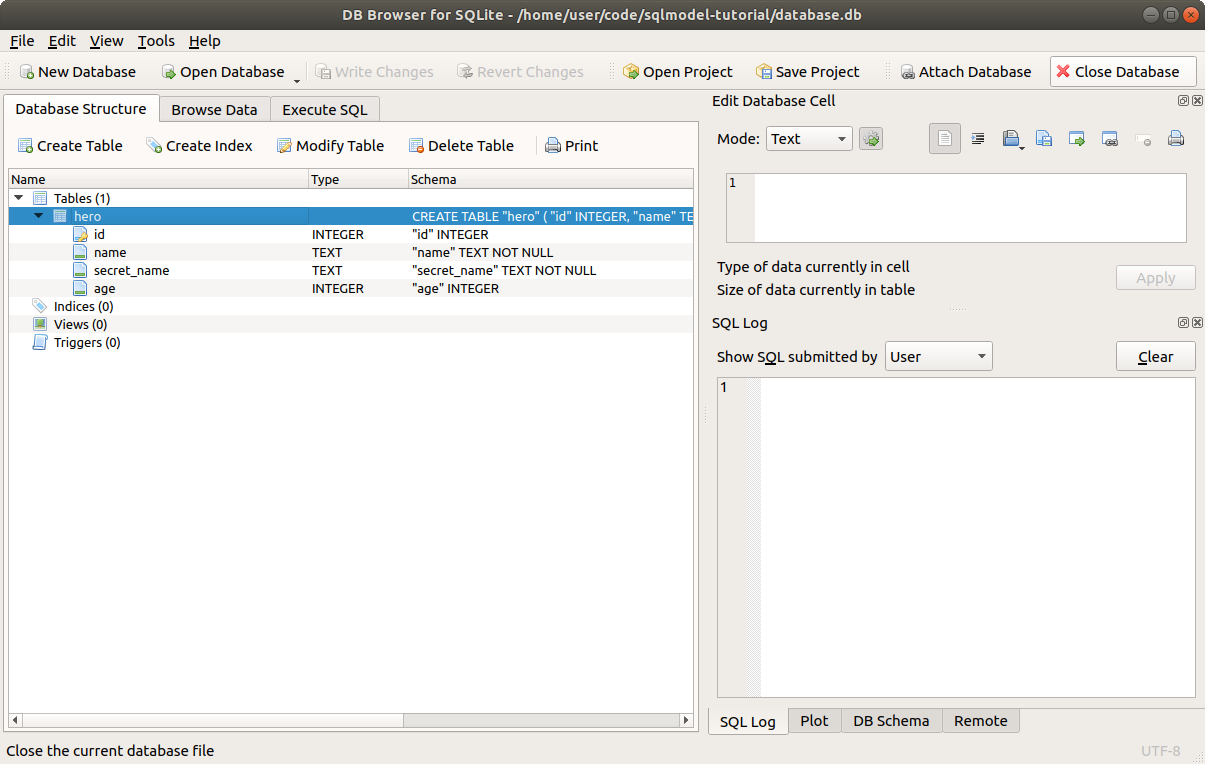

Let's confirm that it's all saved.

First click the button Close Database to close the database.

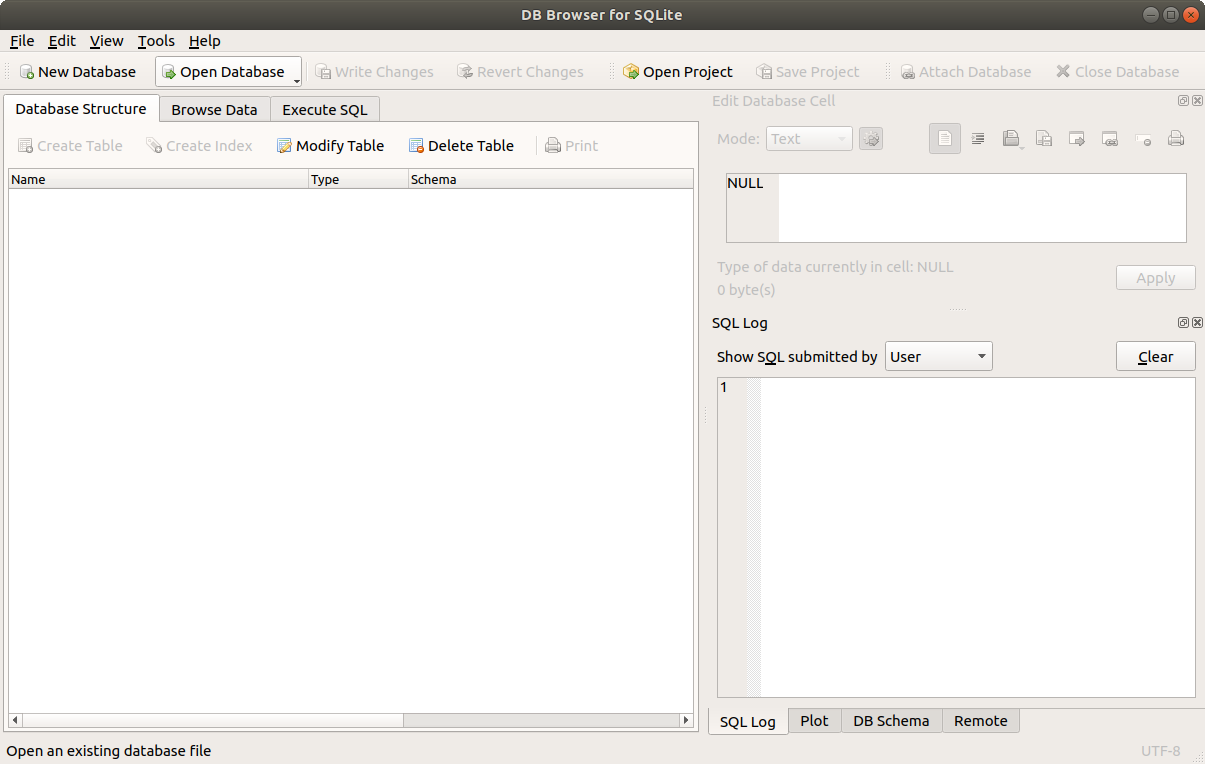

Now click on Open Database to open the database again, and select the same file ./database.db.

You will see again the same table we created.

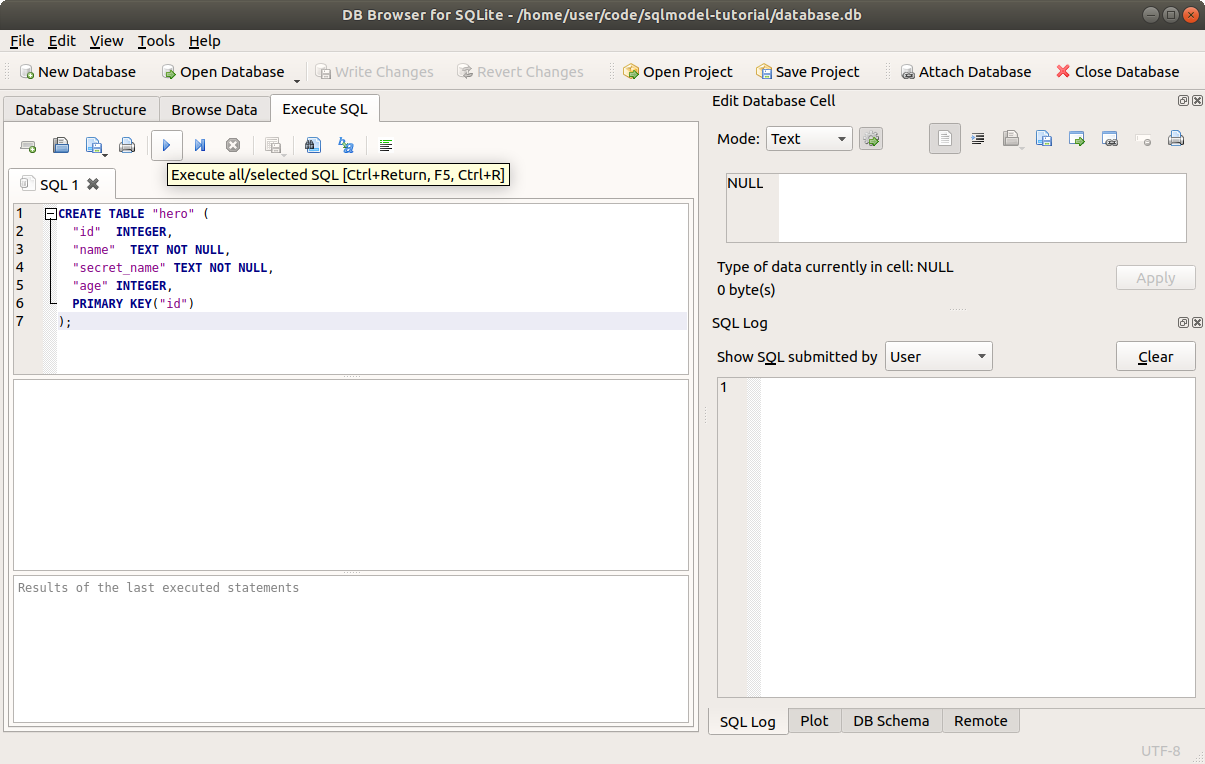

# Create the Table again, with SQL

Now, to see how is it that SQL works, let's create the table again, but with SQL.

Click the Close Database button again.

And delete that ./database.db file in your project directory.

And click again on New Database.

Save the file with the name database.db again.

This time, if you see the dialog to create a new table, just close it by clicking the Cancel button.

And now, go to the tab Execute SQL.

Write the same SQL that was generated in the previous step:

CREATE TABLE "hero" (

"id" INTEGER,

"name" TEXT NOT NULL,

"secret_name" TEXT NOT NULL,

"age" INTEGER,

PRIMARY KEY("id")

);

2

3

4

5

6

7

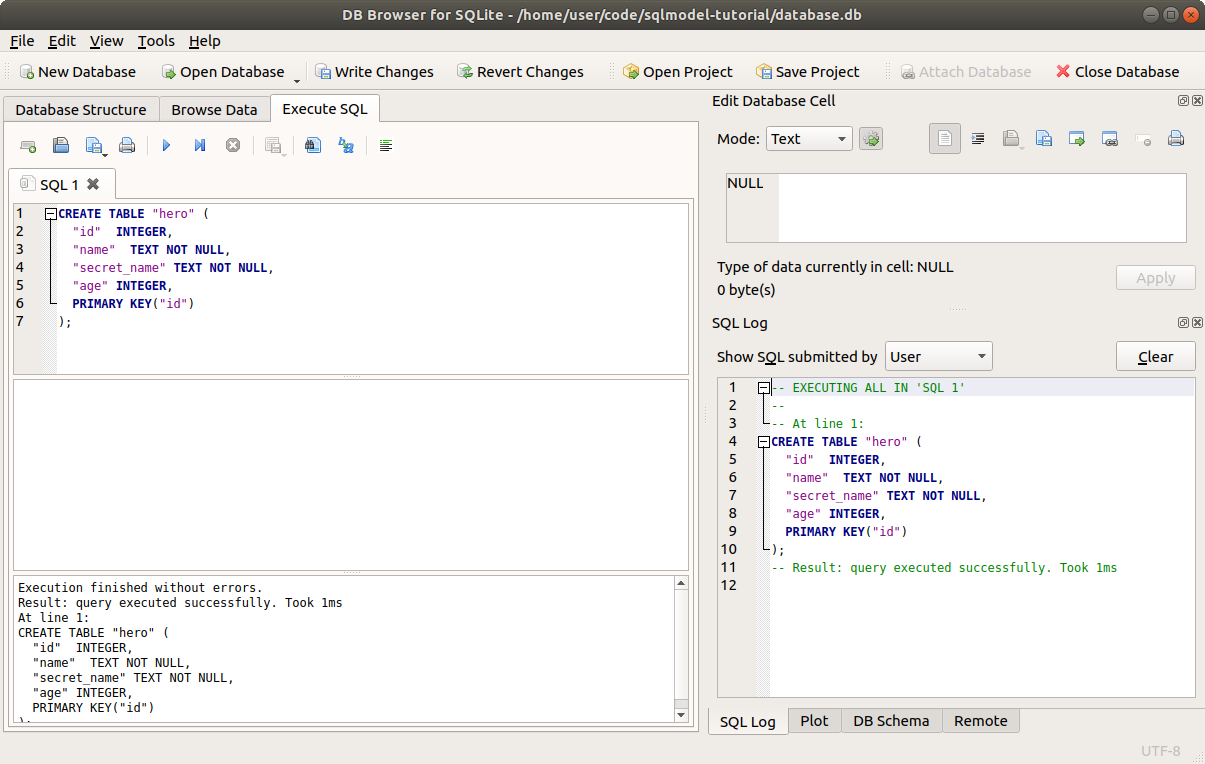

Then click the "Execute all" button.

You will see the "execution finished successfully" message.

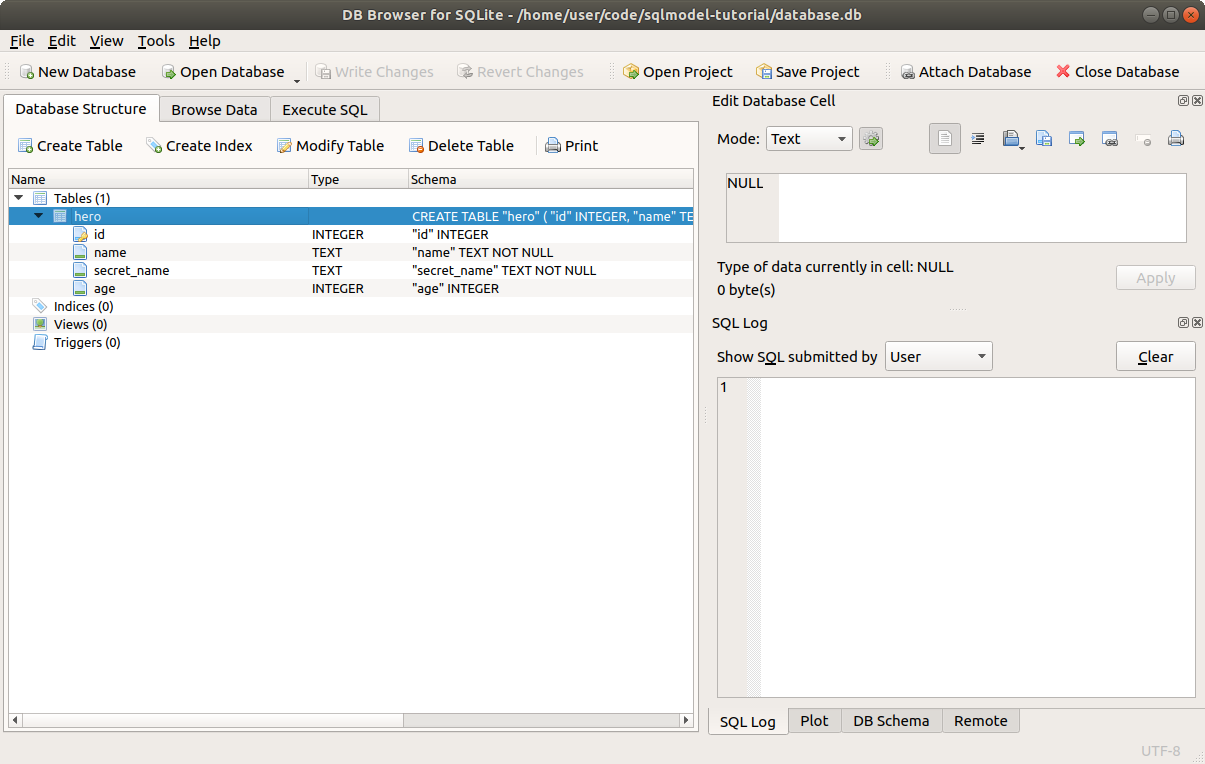

And if you go back to the Database Structure tab, you will see that you effectively created again the same table.

# Learn More SQL

I will keep showing you small bits of SQL through this tutorial. And you don't have to be a SQL expert to use SQLModel.

But if you are curious and want to get a quick overview of SQL, I recommend the visual documentation from SQLite, on SQL As Understood By SQLite.

You can start with CREATE TABLE.

Of course, you can also go and take a full SQL course or read a book about SQL, but you don't need more than what I'll explain here on the tutorial to start being productive with SQLModel.

# Recap

We saw how to interact with SQLite databases in files using DB Browser for SQLite in a visual user interface.

We also saw how to use it to write some SQL directly to the SQLite database. This will be useful to verify the data in the database is looking correctly, to debug, etc.

In the next chapters we will start using SQLModel to interact with the database, and we will continue to use DB Browser for SQLite at the same time to look at the database underneath.

# Create a Table with SQLModel - Use the Engine

Now let's get to the code.

Make sure you are inside of your project directory and with your virtual environment activated as explained in the previous chapter.

We will:

- Define a table with SQLModel

- Create the same SQLite database and table with SQLModel

- Use DB Browser for SQLite to confirm the operations

# Create the Table Model Class

The first thing we need to do is create a class to represent the data in the table.

A class like this that represents some data is commonly called a model.

That's why this package is called SQLModel. Because it's mainly used to create SQL Models.

For that, we will import SQLModel (plus other things we will also use) and create a class Hero that inherits from SQLModel and represents the table model for our heroes:

from sqlmodel import Field, SQLModel, create_engine

class Hero(SQLModel, table=True):

id: int | None = Field(default=None, primary_key=True)

name: str

secret_name: str

age: int | None = None

# Code below omitted

sqlite_file_name = "database.db"

sqlite_url = f"sqlite:///{sqlite_file_name}""

engine = create_engine(sqlite_url, echo=True)

SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine)

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

This class Hero represents the table for our heroes. And each instance we create later will represent a row in the table.

We use the config table=True to tell SQLModel that this is a table model, it represents a table.

It's also possible to have models without table=True, those would be only data models, without a table in the database, they would not be table models.

Those data models will be very useful later, but for now, we'll just keep adding the table=True configuration.

# Define the Fields, Columns

The next step is to define the fields or columns of the class by using standard Python type annotations.

The name of each of these variables will be the name of the column in the table.

And the type of each of them will also be the type of table column:

from sqlmodel import Field, SQLModel, create_engine

class Hero(SQLModel, table=True):

id: int | None = Field(default=None, primary_key=True)

name: str

secret_name: str

age: int | None = None

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Let's now see with more detail these field/column declarations.

# None Fields, Nullable Columns

Let's start with age, notice that it has a type of int | None.

That is the standard way to declare that something "could be an int or None" in Python.

And we also set the default value of age to None.

from sqlmodel import Field, SQLModel, create_engine

class Hero(SQLModel, table=True):

id: int | None = Field(default=None, primary_key=True)

name: str

secret_name: str

age: int | None = None

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

We also define id with int | None. But we will talk about id below.

Because the type is int | None:

- When validating data,

Nonewill be an allowed value forage. - In the database, the column for

agewill be allowed to haveNULL(the SQL equivalent to Python'sNone).

And because there's a default value =None:

- When validating data, this

agefield won't be required, it will beNoneby default. - When saving to the database, the

agecolumn will have aNULLvalue by default.

The default value could have been something else, like = 42.

# Primary Key id

Now let's review the id field. This is the primary key of the table.

So, we need to mark id as the primary key.

To do that, we use the special Field function from sqlmodel and set the argument primary_key=True:

from sqlmodel import Field, SQLModel, create_engine

class Hero(SQLModel, table=True):

id: int | None = Field(default=None, primary_key=True)

name: str

secret_name: str

age: int | None = None

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

That way, we tell SQLModel that this id field/column is the primary key of the table.

But inside the SQL database, it is always required and can't be NULL. Why should we declare it with int | None?

The id will be required in the database, but it will be generated by the database, not by our code.

So, whenever we create an instance of this class (in the next chapters), we will not set the id. And the value of id will be None until we save it in the database, and then it will finally have a value.

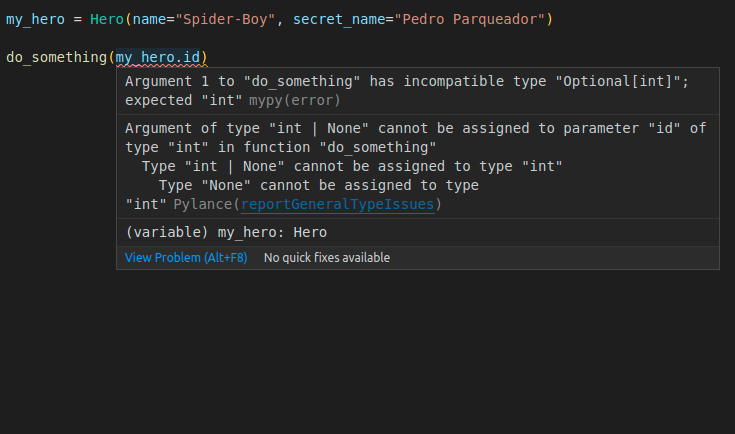

my_hero = Hero(name="Spider-Boy", secret_name="Pedro Parqueador")

do_something(my_hero.id) # Oh no! my_hero.id is None!

# Imagine this saves it to the database

somehow_save_in_db(my_hero)

do_something(my_hero.id) # Now my_hero.id has a value generated in DB

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

So, because in our code (not in the database) the value of id could be None, we use int | None. This way the editor will be able to help us, for example, if we try to access the id of an object that we haven't saved in the database yet and would still be None.

Now, because we are taking the place of the default value with our Field() function, we set the actual default value of id to None with the argument default=None in Field():

Field(default=None)

If we didn't set the default value, whenever we use this model later to do data validation (powered b Pydantic) it would accept a value of None apart from an int, but it would still require pasing that None value. And it would be confusing for for whoever is using this model later (probably us), so better set the default value here.

# Create the Engine

Now we need to create the SQLAlchemy Engine.

It is an object that handles the communication with the database.

If you have a server database (for example PostgreSQL or MySQL), the engine will hold the network connections to that database.

Creating the engine is very simple, just call create_engine() with a URL for the database to use:

from sqlmodel import Field, SQLModel, create_engine

class Hero(SQLModel, table=True):

id: int | None = Field(default=None, primary_key=True)

name: str

secret_name: str

age: int | None = None

sqlite_file_name = "database.db"

sqlite_url = f"sqlite:///{sqlite_file_name}"

engine = create_engine(sqlite_url, echo=True)

SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine)

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

You should normally have a single engine object for your whole application and re-use it everywhere.

There's another related thing called a Session that normally should not be a single object per application. But we will talk about it later.

# Engine Database URL

Each supported database has its own URL type. For example, for SQLite it is sqlite:/// followed by the file path. For example:

sqlite:///database.dbsqlite:///database/local/application.dbsqlite:///db.sqlite

SQLite supports a special database that lives all in memory. Hence, it's very fast, but be careful, the database gets deleted after the program terminates. You can specify this in-memory database by using just two slash characters(//) and no file name:

sqlite://

You can read a lot more about all the databases supported by SQLAlchemy (and that way supported by SQLModel) in the SQLAlchemy documentation.

# Engine Echo

In this example, we are also using the argument echo=True.

It will make the engine print all the SQL statements it executes, which can help you understand what's happening.

It is particularly useful for learning and debugging.

from sqlmodel import Field, SQLModel, create_engine

class Hero(SQLModel, table=True):

id: int | None = Field(default=None, primary_key=True)

name: str

secret_name: str

age: int | None = None

sqlite_file_name = "database.db"

sqlite_url = f"sqlite:///{sqlite_file_name}"

engine = create_engine(sqlite_url, echo=True)

SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine)

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

But in production, you would probably want to remove echo=True:

engine = create_engine(sqlite_url)

# Engine Technical Details

If you didn't know about SQLAlchemy before and are just learning SQLModel, you can probably skip this section, scroll below.

You can read a lot more about the engine in the SQLAlchemy documentation.

SQLModel defines its own create_engine() function. It is the same as SQLAlchemy's create_engine(), but with the difference that it defaults to use future=True (which means that it uses the style of the latest SQLAlchemy, 1.4, and the future 2.0).

And SQLModel's version of create_engine() is type annotated internally, so your editor will be able to help you with autocompletion and inline errors.

# Create the Database and Table

Now everything is in place to finally create the database and table:

from sqlmodel import Field, SQLModel, create_engine

class Hero(SQLModel, table=True):

id: int | None = Field(default=None, primary_key=True)

name: str

secret_name: str

age: int | None = None

sqlite_file_name = "database.db"

sqlite_url = f"sqlite:///{sqlite_file_name}"

engine = create_engine(sqlite_url, echo=True)

SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine)

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Creating the engine doesn't create the database.db file.

But once we run SQLModel.create_all(engine), it creates the database.db file and creates the hero table in that database.

Both things are done in this single step.

Let's unwrap that:

SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine)

# SQLModel MetaData

The SQLModel class has a metadata attribute. It is an instance of a class MetaData.

Whenever you create a class that inherits from SQLModel and is configured with table=True, it is registered in this metadata attribute.

So, by the last line, SQLModel.metadata already has the Hero registered.

# Calling create_all()

This MetaData object at SQLModel.metadata has a create_all() method.

It takes an engine and uses it to create the database and all the tables registered in this MetaData object.

# SQLModel MetaData Order Matters

This also means that you have to call SQLModel.metadata.create_all() after the code that creates new model classes inheriting from SQLModel.

For example, let's imagine you do this:

- Create the models in one Python file

models.py - Create the engine object in a file

db.py - Create your main app and call

SQLModel.metadata.create_all()inapp.py

If you only imported SQLModel and tried to call SQLModel.metadata.create_all() in app.py, it would not create your tables:

# This wouldn't work!

from sqlmodel import SQLModel

from .db import engine

SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine)

2

3

4

5

6

It wouldn't work because when you import SQLModel alone, Python doesn't execute all the code creating the classes inheriting from it (in our example, the class Hero), so SQLModel.metadata is still empty.

But if you import the models before calling SQLModel.metadata.create_all(), it will work:

from sqlmodel import SQLModel

from . import models

from .db import engine

SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine)

2

3

4

5

6

This would work because by importing the models, Python executes all the code creating the classes inheriting from SQLModel and registering them in the SQLModel.metadata.

As an alternative, you could import SQLModel and your models inside of db.py:

# db.py

from sqlmodel import SQLModel, create_engine

from . import models

sqlite_file_name = "database.db"

sqlite_url = f"sqlite:///{sqlite_file_name}"

engine = create_engine(sqlite_url)

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

And then import SQLModel from db.py in app.py, and there call SQLModel.metadata.create_all():

# app.py

from .db import engine, SQLModel

SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine)

2

3

4

The import of SQLModel from db.py would work because SQLModel is also imported in db.py.

And this trick would work correctly and create the tables in the database because by importing SQLModel from db.py, Python executes all the code creating the classes that inherit from SQLModel in that db.py file, for example, the class Hero.

# Migrations

For this simple example, and for most of the Tutorial - User Guide, using SQLModel.metadata.create_all() is enough.

But for a production system you would probably want to use a system to migrate the database.

This would be useful and important, for example, whenever you add or remove a column, add a new table, change a type, etc.

But you will learn about migrations later in the Advanced User Guide.

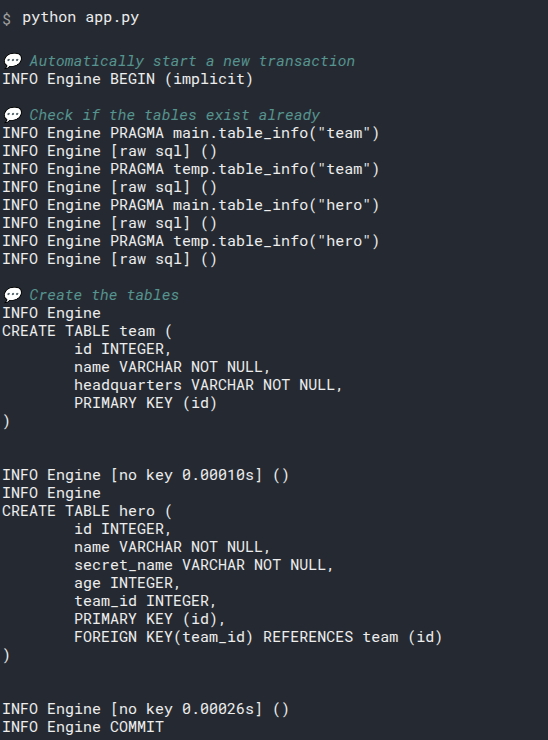

# Run The Program

Let's run the program to see it all working.

Put the code it in a file app.py if you haven't already.

from sqlmodel import Field, SQLModel, create_engine

class Hero(SQLModel, table=True):

id: int | None = Field(default=None, primary_key=True)

name: str

secret_name: str

age: int | None = None

sqlite_file_name = "database.db"

sqlite_url = f"sqlite:///{sqlite_file_name}"

engine = create_engine(sqlite_url, echo=True)

SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine)

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Remember to activate the virtual environment before running it.

Now run the program with Python:

# We set echo = True, so this will show the SQL code

python app.py

# First, some boilerplate SQL that we are not that interested in

INFO Engine BEGIN (implicit)

INFO Engine PRAGMA main.table_info("hero")

INFO Engine [raw sql] ()

INFO Engine PRAGMA temp.table_info("hero")

INFO Engine [raw sql] ()

INFO Engine

# Finally, the glorious SQL to create the table

CREATE TABLE hero (

id INTEGER,

name VARCHAR NOT NULL,

secret_name VARCHAR NOT NULL,

age INTEGER,

PRIMARY KEY (id)

)

# More SQL boilerplate

INFO Engine [no key 0.00020s] ()

INFO Engine COMMIT

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

I simplified output above a bit to make it easier to read.

But in reality, instead of showing:

INFO Engine BEGIN (implicit)

it would show something like:

2021-07-25 21:37:39,175 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.Engine BEGIN (implicit)

# TEXT or VARCHAR

In the example in the previous chapter we created the table using TEXT for some columns.

But in this output SQLAlchemy is using VARCHAR instead. Let's see what's going on.

Remember that each SQL Database has some different variations in what they support?

This is one of the differences. Each database supports some particular data types, like INTEGER and TEXT.

Some databases have some particular types that are special for certain things. For example, PostgreSQL and MySQL support BOOLEAN for values of True and False. SQLite accepts SQL with booleans, even when defining table columns, but what it actually uses internally are INTEGERs, with 1 to represent True and 0 to represent False.

The same way, there are several possible types for storing strings. SQLite uses the TEXT type. But other databases like PostgreSQL and MySQL use the VARCHAR type by default, and VARCHAR is one of the most common data types.

VARCHAR comes from variable length character.

SQLAlchemy generates the SQL statements to create tables using VARCHAR, and then SQLite receives them, and internally converts them to TEXTs.

Additional to the difference between those two data types, some databases like MySQL require setting a maximum length for the VARCHAR types, for example VARCHAR(255) sets the maximum number of characters to 255.

To make it easier to start using SQLModel right away independent of the database you use (even with MySQL), and without any extra configurations, by default, str fields are interpreted as VARCHAR in most databases and VARCHAR(255) in MySQL, this way you know the same class will be compatible with the most popular databases without extra effort.

You will learn how to change the maximum length of string columns later in the Advanced Tutorial - User Guide.

# Verify the Database

Now, open the database with DB Browser for SQLite, you will see that the program created the table hero just as before.

# Refector Data Creation

Now let's restructure the code a bit to make it easier to reuse, share, and test later.

Let's move the code that has the main side effects, that changes data (creates a file with a database and a table) to a function.

In this example it's just the SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine).

Let's put it in a function create_db_and_tables():

from sqlmodel import Field, SQLModel, create_engine

class Hero(SQLModel, table=True):

id: int | None = Field(default=None, primary_key=True)

name: str

secret_name: str

age: int | None = None

sqlite_file_name = "database.db"

sqlite_url = f"sqlite:///{sqlite_file_name}"

engine = create_engine(sqlite_url, echo=True)

def create_db_and_tables():

SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine)

if __name__ == "__main__":

create_db_and_tables()

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

If SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine) was not in a function and we tried to import something from this module (from this file) in another, it would try to create the database and table every time we executed that other file that imported this module.

We don't want that to happen like that, only when we intend it to happen, that's why we put it in a function, because we can make sure that the tables are created only when we call that function, and not when this module is imported somewhere else.

Now we would be able to, for example, import the Hero class in some other file without having those side effects.

The function is called create_db_and_tables() because we will have more tables in the future with other classes apart from Hero.

# Create Data as a Script

We prevented the side affects when importing something from your app.py file.

But we still want it to create the database and table when we call it with Python directly as an independent script from the terminal, just as above.

Think of the word script and program as interchangeable.

The word script often implies that the code could be run independently and easily. Or in some cases it refers to a relatively simple program.

For that we can use the special variable __name__ in an if block:

from sqlmodel import Field, SQLModel, create_engine

class Hero(SQLModel, table=True):

id: int | None = Field(default=None, primary_key=True)

name: str

secret_name: str

age: int | None = None

sqlite_file_name = "database.db"

sqlite_url = f"sqlite:///{sqlite_file_name}"

engine = create_engine(sqlite_url, echo=True)

def create_db_and_tables():

SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine)

if __name__ == "__main__":

create_db_and_tables()

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

# About __name__ == __main__

The main purpose of the __name__ == "__main__" is to have some code that is executed when your file is called with:

python app.py

but is not called when another file imports it, like in:

from app import Hero

That if block using if __name__ == "__main__": is sometimes called the "main block".

The official name (in the Python docs) is "Top-level script environment".

# More details

Let's say your file is named myapp.py.

If you run it with:

python myapp.py

then the internal variable __name__ in your file, created automatically by Python, will have as value the string "__main__".

So, the function in:

if __name__ == "__main__":

create_db_and_tables()

2

will run.

This won't happen if you import that module (file).

So, if you have another file importer.py with:

from myapp import Hero

# Some more code

2

3

in that case, the automatic variable inside of myapp.py will not have the variable __name__ with a value of "__main__".

So, the line:

if __name__ == "__main__":

create_db_and_tables()

2

will not be executed.

For more information, check the official Python docs.

# Last Review

After those changes, you could run it again, and it would generate the same output as before.

But now we can import things from this module in other files.

Now, let's give the code a final look:

# Import the things we will need from sqlmodel: Field, SQLModel, create_engine

from sqlmodel import Field, SQLModel, create_engine

# Create the Hero model class, representing the hero table in the database.

# And also mark this class as a table model with table=True

class Hero(SQLModel, table=True):

# Create the id field:

# It could be None until the database assigns a value to it, so we annotate it with Optional.

# It is a primary key, so we use Field() and the argument primary_key=True

id: int | None = Field(default=None, primary_key=True)

# Create the name field

# It is required, so there's no default value, and it's not Optional

name: str

# Create the secret_name field

# Also required

secret_name: str

# Create the age field.

# It is not required, the default value is None

# In the database, the default value will be NULL, the SQL equivalent of None.

# As this field could be None (and NULL in the database), we annotate it with Optional.

age: int | None = None

# Write the name of the database file

sqlite_file_name = "database.db"

# Use the name of the database file to create the database URL

sqlite_url = f"sqlite:///{sqlite_file_name}"

# Create the engine using the URL

# This doesn't create the database yet, no file or table is created at this point,

# only the engine object that will handle the connections with this specific database,

# and with specific support for SQLite (based on the URL).

engine = create_engine(sqlite_url, echo=True)

# Put the code that creates side effects in a function

# In this case, only one line that creates the database file with the table.

def create_db_and_tables():

# Create all the tables that were automatically registered in SQLModel.metadata

SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine)

# Add a main block, or "Top-level script environment".

# And put some logic to be executed when this is called directly with Python, as in:

# python app.py

if __name__ == "__main__":

# In this main block, call the function that creates the database file and the table.

# This way when we call it with:

# python app.py

create_db_and_tables()

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

# Recap

We learn how to use SQLModel to define how a table in the database should look like, and we created a database and a table using SQLModel.

We also refactored the code to make it easier to reuse, share, and test later.

In the next chapters we will see how SQLModel will help us interact with SQL databases from code.

# Create Rows - Use the Session - INSERT

Now that we have a database and a table, we can start adding data.

Here's reminder of the table would look like, this is the data we want to add:

| id | name | secret_name | age |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Deadpond | Dive Wilson | null |

| 2 | Spider-Boy | Pedro Parqueador | null |

| 3 | Rusty-Man | Tommy Sharp | 48 |

# Create Table and Database

We will continue from where we left off in the last chapter.

This is the code we had to create the database and table, nothing new here:

# Import the things we will need from sqlmodel: Field, SQLModel, create_engine

from sqlmodel import Field, SQLModel, create_engine

# Create the Hero model class, representing the hero table in the database.

# And also mark this class as a table model with table=True

class Hero(SQLModel, table=True):

# Create the id field:

# It could be None until the database assigns a value to it, so we annotate it with Optional.

# It is a primary key, so we use Field() and the argument primary_key=True

id: int | None = Field(default=None, primary_key=True)

# Create the name field

# It is required, so there's no default value, and it's not Optional

name: str

# Create the secret_name field

# Also required

secret_name: str

# Create the age field.

# It is not required, the default value is None

# In the database, the default value will be NULL, the SQL equivalent of None.

# As this field could be None (and NULL in the database), we annotate it with Optional.

age: int | None = None

# Write the name of the database file

sqlite_file_name = "database.db"

# Use the name of the database file to create the database URL

sqlite_url = f"sqlite:///{sqlite_file_name}"

# Create the engine using the URL

# This doesn't create the database yet, no file or table is created at this point,

# only the engine object that will handle the connections with this specific database,

# and with specific support for SQLite (based on the URL).

engine = create_engine(sqlite_url, echo=True)

# Put the code that creates side effects in a function

# In this case, only one line that creates the database file with the table.

def create_db_and_tables():

# Create all the tables that were automatically registered in SQLModel.metadata

SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine)

# Add a main block, or "Top-level script environment".

# And put some logic to be executed when this is called directly with Python, as in:

# python app.py

if __name__ == "__main__":

# In this main block, call the function that creates the database file and the table.

# This way when we call it with:

# python app.py

create_db_and_tables()

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

Now that we can create the database and the table, we will continue from this point and add more code on the same file to create the data.

# Create Data with SQL

Before working with Python code, let's see how we can create data with SQL.

Let's say we want to insert the record/row for Deadpond into our database.

We can do this with the following SQL code:

INSERT INTO "hero" ("name", "secret_name") VALUES ("Deadpond", "Dive Wilson");

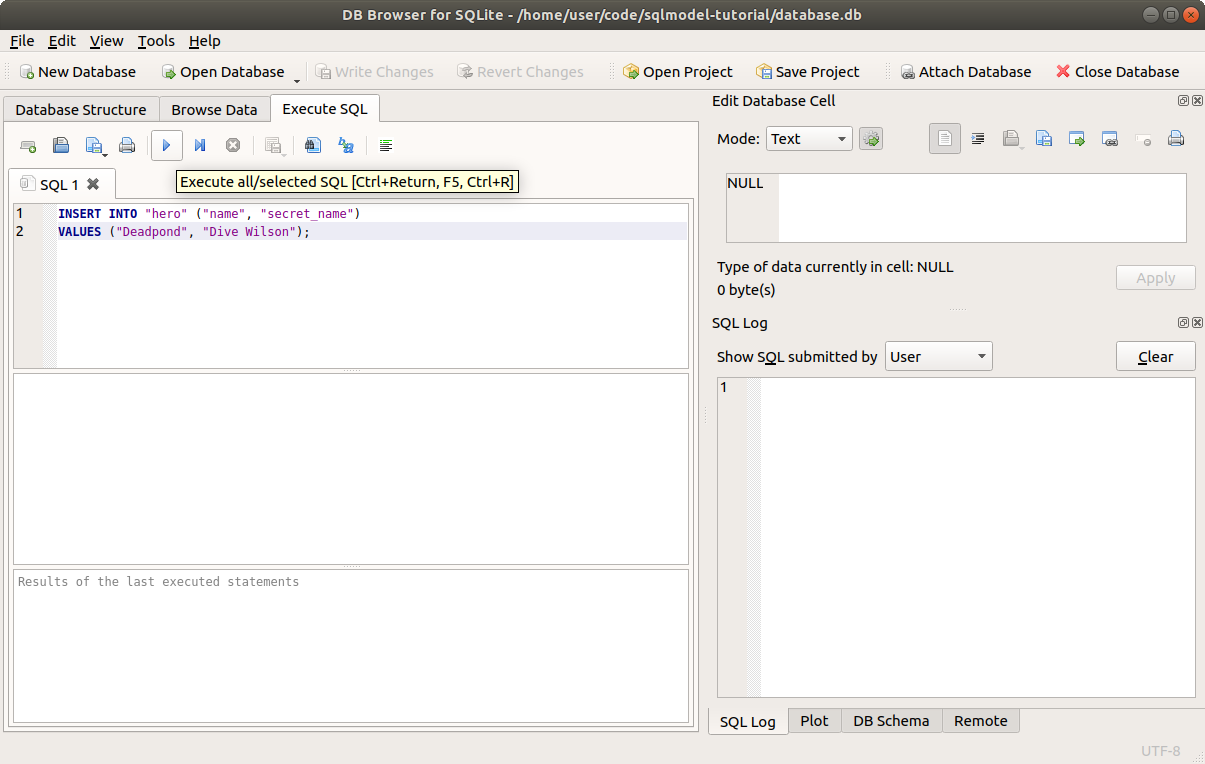

# Try it in DB Explorer for SQLite

You can try that SQL statement in DB Explorer for SQLite.

Make sure to open the same database we already created by clicking Open Database and selecting the same database.db file.

Then go to the Execute SQL tab and copy the SQL from above.

It would look like this:

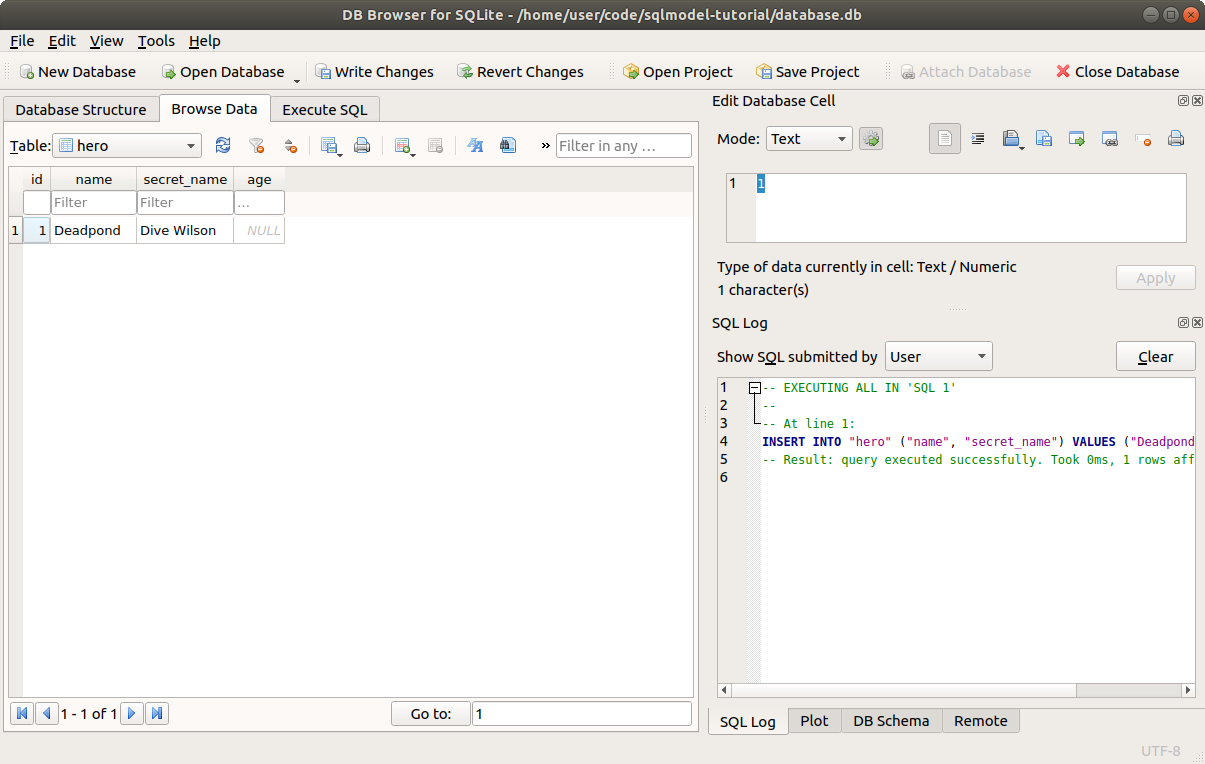

Click the "Execute all" button. Then you can go to the Browse Data tab, and you will see your newly created record/row:

# Data in a Database and Data in Code

When working with a database (SQL or any other type) in a programming language, we will always have some data in memory, in objects and variables we create in our code, and there will be some data in the database.

We are constantly getting some of the data from the database and putting it in memory, in variables.

The same way, we are constantly creating variables and objects with data in our code, that we then want to save in the database, so we send it somehow.

In some cases, we can even create some data in memory and then change it and update it before saving it in the database.

We might even decide with some logic in the code that we no longer want to save the data in the database, and then just remove it. And we only handled that data in memory, without sending it back and forth to the database.

SQLModel does all it can (actually via SQLAlchemy) to make this interaction as simple, intuitive, and familiar or "close to programming" as possible.

But that division of the two places where some data might be at each moment in time (in memory or in the database) is always there. And it's important for you to have it in mind.

# Create Data with Python and SQLModel

Now let's create that same row in Python.

First, remove that file database.db so we can start from a clean slate.

Because we have Python code executing with data in memory, and the database is an independent system (an external SQLite file, or an external database server), we need to perform two steps:

- create the data in Python, in memory (in a variable)

- save/send the data to the database

# Create a Model Instance

Let's start with the first step, create the data in memory.

We already created a class Hero that represents the hero table in the database.

Each instance we create will represent the data in a row in the database.

So, the first steop is to simply create an instance of Hero.

We'll create 3 right away, for the 3 heros:

from sqlmodel import Field, Session, SQLModel, create_engine

class Hero(SQLModel, table=True):

id: int | None = Field(default=None, primary_key=True)

name: str

secret_name: str

age: int | None = None

sqlite_file_name = "database.db"

sqlite_url = f"sqlite:///{sqlite_file_name}"

engine = create_engine(sqlite_url, echo=True)

def create_db_and_tables():

SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine)

def create_heroes():

hero_1 = Hero(name="Deadpond", secret_name="Dive Wilson")

hero_2 = Hero(name="Spider-Boy", secret_name="Pedro Parqueador")

hero_3 = Hero(name="Rusty-Man", secret_name="Tommy Sharp", age=48)

with Session(engine) as session:

session.add(hero_1)

session.add(hero_2)

session.add(hero_3)

session.commit()

def main():

create_db_and_tables()

create_heroes()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

We are putting that in a function create_heroes(), to call it later once we finish it.

If you are trying the code interactively, you could also write that directly.

# Create a Session

Up to now, we have only used the engine to interact with the database.

The engine is that single object that we share with all the code, and that is in charge of communicating with database, handling the connections (when using a server database like PostgreSQL or MySQL), etc.

But wen working with SQLModel you will mostly use another tool that sits on top, the Session.

In contrast to the engine that is one for the whole application, we create a new session for each group of operations with the database that belong together.

In fact, the session needs and uses an engine.

For example, if we have a web application, we would normally have a single session per request.

We would re-use the same engine in all the code, everywhere in the application (shared by all the requests). But for each request, we would create and use a new session. And once the request is done, we would close the session.

The first step is to import the Session class:

from sqlmodel import Field, Session, SQLModel, create_engine

# Code below omitted

2

3

Then we can create a new session:

# Code above omitted

def create_heroes():

hero_1 = Hero(name="Deadpond", secret_name="Dive Wilson")

hero_2 = Hero(name="Spider-Boy", secret_name="Pedro Parqueador")

hero_3 = Hero(name="Rusty-Man", secret_name="Tommy Sharp", age=48)

session = Session(engine)

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

The new Session takes an engine as a parameter. And it will use the engine underneath.

We will see a better way to create a session using a with block later.

# Add Model Instances to the Session

Now that we have some hero model instances (some objects in memory) and a session, the next step is to add them to the session:

# Code above omitted

def create_heroes():

hero_1 = Hero(name="Deadpond", secret_name="Dive Wilson")

hero_2 = Hero(name="Spider-Boy", secret_name="Pedro Parqueador")

hero_3 = Hero(name="Rusty-Man", secret_name="Tommy Sharp", age=48)

session = Session(engine)

session.add(hero_1)

session.add(hero_2)

session.add(hero_3)

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

By this point, our heroes are not stored in the database yet.

And this is one of the cases where having a session independent of an engine makes sense.

The session is holding in memory all the objects that should be saved in the database later.

And once we are ready, we can commit those changes, and then the session will use the engine underneath to save all the data by sending the appropriate SQL to the database, and that way it will create all the rows. All in a single batch.

This makes the interactions with the database more efficient (plus some extra benefits).

Technical Details

The session will create a new transaction and execute all the SQL code in that transaction.

This ensure that the data is saved in a single batch, and that it will all succeed or all fail, but it won't leave the database in a broken state.

# Commit the Session Changes

Now that we have the heroes in the session and that we are ready to save all that to the database, we can commit the changes:

# Code above omitted

def create_heroes():

hero_1 = Hero(name="Deadpond", secret_name="Dive Wilson")

hero_2 = Hero(name="Spider-Boy", secret_name="Pedro Parqueador")

hero_3 = Hero(name="Rusty-Man", secret_name="Tommy Sharp", age=48)

session = Session(engine)

session.add(hero_1)

session.add(hero_2)

session.add(hero_3)

session.commit()

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Once this line is executed, the session will use the engine to save all the data in the database by sending the corresponding SQL.

# Create Heroes as a Script

The function to create the heroes is now ready.

Now we just need to make sure to call it when we run this program with Python directly.

We already had a main block like:

if __name__ == "__main__":

create_db_and_tables()

2

We could add the new function there, as:

if __name__ == "__main__":

create_db_and_tables()

create_heroes()

2

3

But to keep things a bit more organized, let's instead create a new function main() that will contain all the code that should be executed when called as an independent script, and we can put there the previous function create_db_and_tables(), and add the new function create_heroes():

# Code above omitted

def main():

create_db_and_tables()

create_heroes()

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

And then we can call that single main() function from that main block:

# Code above omitted

def main():

create_db_and_tables()

create_heroes()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

By having everything that should happen when called as a script in a single function, we can easily add more code later on.

And some other code could also import and use this same main() function if it was necessary.

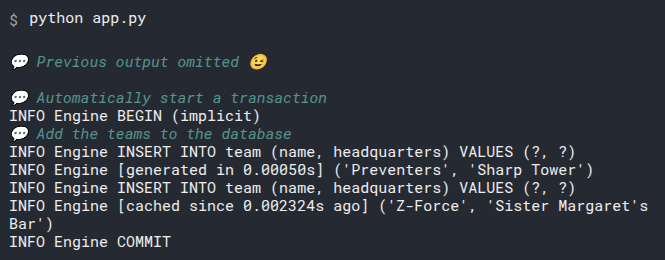

# Run the Script

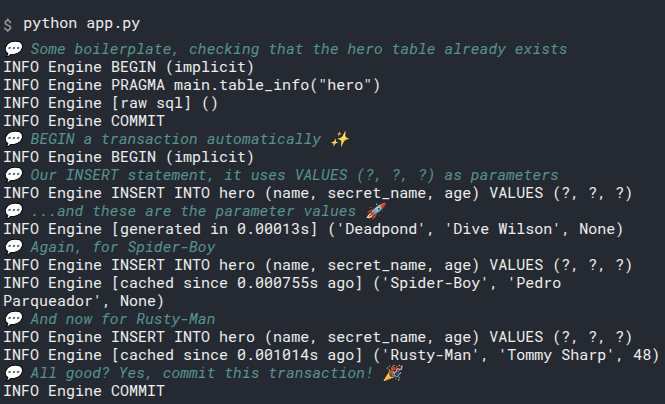

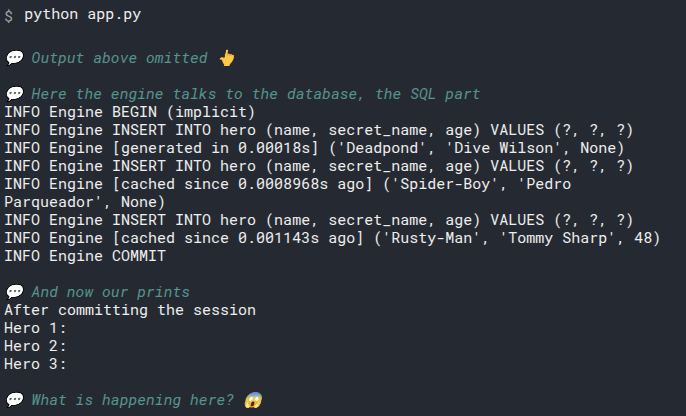

Now we can run our program as a script from the console.

Because we created the engine with echo=True, it will print out all the SQL code that it is executing:

If you have ever used Git, this works very similarly.

We use session.add() to add new objects (model instances) to the session (similar to git add).

And that ends up in a group of data ready to be saved, but not saved yet.

We can make more modifications, add more objects, etc.

And once we are ready, we can commit all the changes in a single step (similar to git commit).

# Close the Session

The session holds some resources, like connections from the engine.

So once we are done with the session, we should close it to make it release those resources and finish its cleanup:

# Code above omitted

def create_heroes():

hero_1 = Hero(name="Deadpond", secret_name="Dive Wilson")

hero_2 = Hero(name="Spider-Boy", secret_name="Pedro Parqueador")

hero_3 = Hero(name="Rusty-Man", secret_name="Tommy Sharp", age=48)

session = Session(engine)

session.add(hero_1)

session.add(hero_2)

session.add(hero_3)

session.commit()

session.close()

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

But what happens if we forget to close the session?

Or if there's an exception in the code and it never reaches the session.close()?

For that, there's a better way to create and close the session, using a with block.

# A Session in a with Block

It's good to know how the Session works and how to create and close it manually. It might be useful if, for example, you want to explore the code in an interactive session (for example with Jupyter).

But there's a better way to handle the session, using a with block:

# Code above omitted

def create_heroes():

hero_1 = Hero(name="Deadpond", secret_name="Dive Wilson")

hero_2 = Hero(name="Spider-Boy", secret_name="Pedro Parqueador")

hero_3 = Hero(name="Rusty-Man", secret_name="Tommy Sharp", age=48)

with Session(engine) as session:

session.add(hero_1)

session.add(hero_2)

session.add(hero_3)

session.commit()

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

This is the same as creating the session manually and then manually closing it. But here, using a with block, it will be automatically created when starting the with block and assigned to the variable session, and it will be automatically closed after the with block is finished.

And it will work even if there's an exception in the code.

# Review All the Code

Let's give this whole file a final look.

You already know all of the first part for creating the Hero model class, the engine, and creating the database and table.

Let's focus on the new code:

from sqlmodel import Field, Session, SQLModel, create_engine

class Hero(SQLModel, table=True):

id: int | None = Field(default=None, primary_key=True)

name: str

secret_name: str

age: int | None = None

sqlite_file_name = "database.db"

sqlite_url = f"sqlite:///{sqlite_file_name}"

engine = create_engine(sqlite_url, echo=True)

def create_db_and_tables():

SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine)

# We use a function create_heroes() to put this logic together

def create_heroes():

# Create each of the objects/instances of the Hero model

# Each of them represents the data for one row.

hero_1 = Hero(name="Deadpond", secret_name="Dive Wilson")

hero_2 = Hero(name="Spider-Boy", secret_name="Pedro Parqueador")

hero_3 = Hero(name="Rusty-Man", secret_name="Tommy Sharp", age=48)

# Use a with block to create a Session using the engine.

# The new session will be assigned to the variable session.

# And it will be automatically closed when the with block is finished.

with Session(engine) as session:

# And each of the objects/instances to the session.

# Each of these objects represents a row in the database.

# They are all waiting there in the session to be saved.

session.add(hero_1)

session.add(hero_2)

session.add(hero_3)

# Commit the changes to the database.

# This will actually send the data to the database.

# It will start a transaction automatically and save all the data in a single batch.

session.commit()

# By this point, after the with block is finished, the session is automatically closed.

# We have a main() function with all the code that should be executed when the program is called as a script from the

# console.

# That way we can add more code later to this function.

# We then put this function main() in the main block below.

# And as it is a single function, other Python files could import it and call it directly.

def main():

# In this main() function, we are also creating the database and the tables.

# In the previous version, this function was called directly in the main block.

# But now it is just called in the main() function.

create_db_and_tables()

# And now we are also creating the heroes in this main() function.

create_heroes()

# We still have a main block to execute some code when the program is run as a script from the command line, like:

# python app.py

if __name__ == "__main__":

# There's a single main() function now that contains all the code that should be executed when running the program

# from the console.

# So this is all we need to have in the main block. Just call the main() function.

main()

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

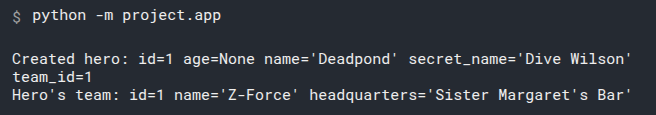

You can now put it in a app.py file and run it with Python. And you will see an output like the one shown above.

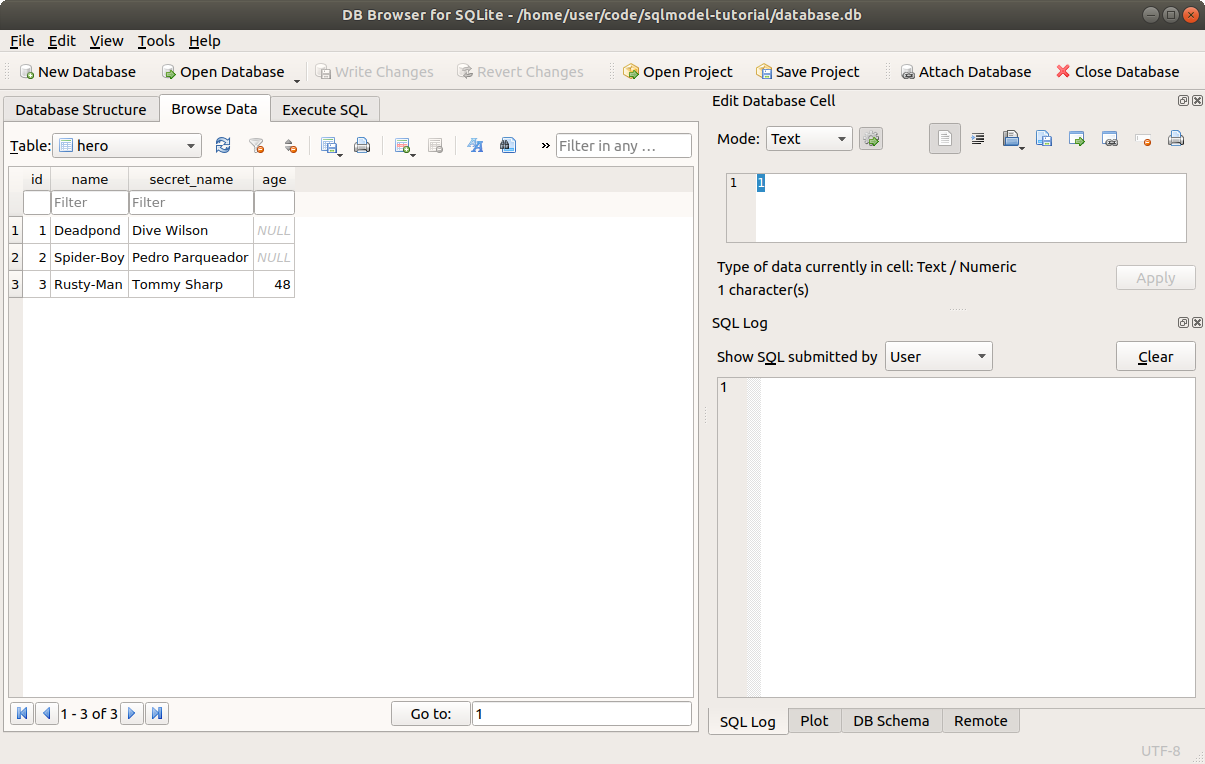

After that, if you open the database with DB Browser for SQLite, you will see the data you just created in the Browser Data tab:

# What's Next

Now you know how to add rows to the database.

Now is a good time to understand better why the id field can't be NULL on the database because it's a primary key, but actually can be None in the Python code.

# Automatic IDs, None Defaults, and Refreshing Data

In the previous chapter, we saw how to add rows to the database using SQLModel.

Now let's talk a bit about why the id field can't be NULL on the database because it's a primary key, and we declare it using Field(primary_key=True).

But the same id field actually can be NULL in the Python code, so we declare the type with int | None, and set the default value to Field(default=None):

# Code above omitted

class Hero(SQLModel, table=True):

id: int | None = Field(default=None, primary_key=True)

name: str

secret_name: str

age: int | None = None

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Next, I'll show you a bit more about the synchronization of data between the database and the Python code.

When do we get an actual int from the database in that id field? Let's see all that.

# Create a New Hero Instance

When we create a new Hero instance, we don't set the id:

# Code above omitted

def create_heroes():

hero_1 = Hero(name="Deadpond", secret_name="Dive Wilson")

hero_2 = Hero(name="Spider-Boy", secret_name="Pedro Parqueador")

hero_3 = Hero(name="Rusty-Man", secret_name="Tommy Sharp", age=48)

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# How int | None Helps

Because we don't set the id, it takes the Python's default value of None that we set in Field(default=None).

This is the only reason why we define it with int | None and with a default value of None.

Because at this point in the code, before interacting with the database, the Python value could actually be None.

If we assumed that the id was always an int and added the type annotation without int | None, we could end up writing broken code, like:

next_hero_id = hero_1.id + 1

If we ran this code before saving the hero to the database and the hero_1.id was still None, we would get an error like:

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'NoneType' and 'int'

But by declaring it with int | None, the editor will help us to avoid writing broken code by showing us a warning telling us that the code could be invalid if hero_1.id is None.

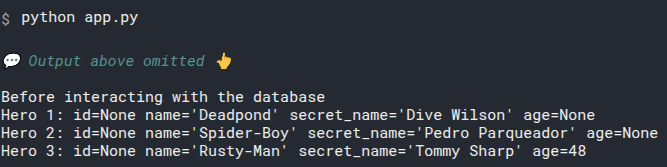

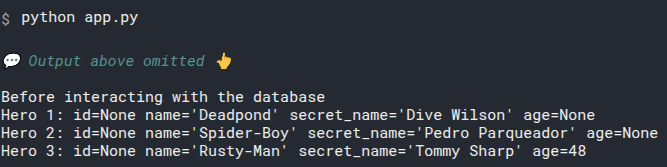

# Print the Default id Values

We can confirm that by printing our heroes before adding them to the database:

# Code above omitted

def create_heroes():

hero_1 = Hero(name="Deadpond", secret_name="Dive Wilson")

hero_2 = Hero(name="Spider-Boy", secret_name="Pedro Parqueador")

hero_3 = Hero(name="Rusty-Man", secret_name="Tommy Sharp", age=48)

print("Before interacting with the database")

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

print("Hero 2:", hero_2)

print("Hero 3:", hero_3)

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

That will output:

Notice they all have id=None.

That's the default value we defined in the Hero model class.

What happens when we add these objects to the session?

# Add the Objects to the Session

After we add the Hero instance objects to the session, the IDs are still None.

We can verify by creating a session using a with block and adding the objects. And then printing them again:

# Code above omitted

def create_heroes():

hero_1 = Hero(name="Deadpond", secret_name="Dive Wilson")

hero_2 = Hero(name="Spider-Boy", secret_name="Pedro Parqueador")

hero_3 = Hero(name="Rusty-Man", secret_name="Tommy Sharp", age=48)

print("Before interacting with the database")

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

print("Hero 2:", hero_2)

print("Hero 3:", hero_3)

with Session(engine) as session:

session.add(hero_1)

session.add(hero_2)

session.add(hero_3)

print("After adding to the session")

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

print("Hero 2:", hero_2)

print("Hero 3:", hero_3)

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

This will, again, output the ids of the objects as None:

As we saw before, the session is smart and doesn't talk to the database every time we prepare something to be changed, only after we are ready and tell it to commit the changes it goes and sends all the SQL to the database to store the data.

# Commit the Changes to the Database

Then we can commit the changes in the session, and print again:

# Code above omitted

with Session(engine) as session:

session.add(hero_1)

session.add(hero_2)

session.add(hero_3)

print("After adding to the session")

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

print("Hero 2:", hero_2)

print("Hero 3:", hero_3)

session.commit()

print("After committing the session")

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

print("Hero 2:", hero_2)

print("Hero 3:", hero_3)

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

And now, something unexpected happens, look at the output, it seems as if the Hero instance objects had no data at all:

What happens is that SQLModel (actually SQLAlchemy) is internally marking those objects as "expired", they don't have the latest version of their data. This is because we could have some fields updated in the database, for example, imagine a field updated_at: datetime that was automatically updated when we saved changes.

The same way, other values could have changed, so the option the session has to be sure and safe is to just internally mark the objects are expired.

And then, next time we access each attibute, for example with:

current_hero_name = hero_1.name

SQLModel (actually SQLAlchemy) will make sure to contact the database and get the most recent version of the data, updating that field name in our object and then making it available for the rest of the Python expression. In the example above, at that point, Python would be able to continue executing and use that hero_1.name value (just updated) to put it in the variable current_hero_name.

All this happens automatically and behind the scenes.

And here's the funny and strange thing with our example:

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

We didn't access the object's attributes, like hero.name. We only accessed the entire object and printed it, so SQLAlchemy has no way of knowing that we want to access this object's data.

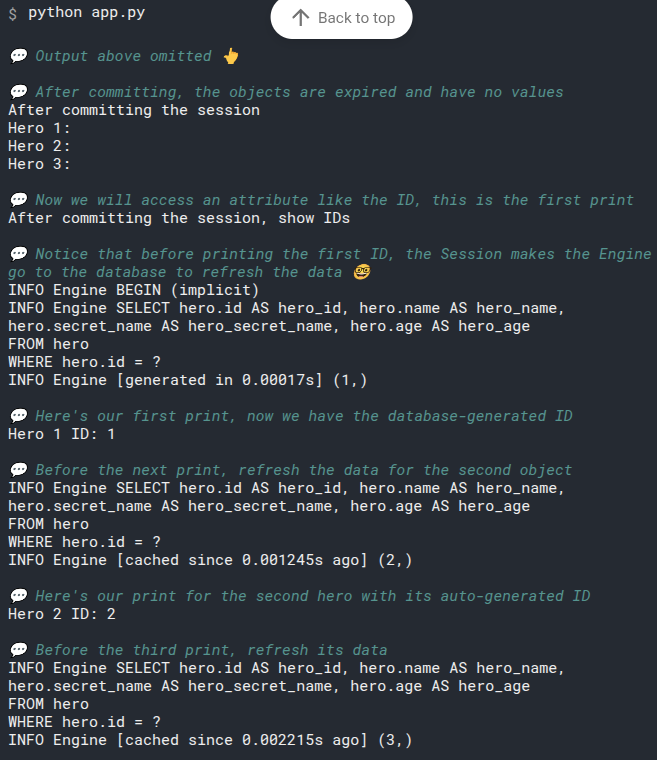

# Print a Single Field

To confirm and understand how this automatic expiration and refresh of data when accessing attributes work, we can print some individual fields (instance attributes):

# Code above omitted

with Session(engine) as session:

session.add(hero_1)

session.add(hero_2)

session.add(hero_3)

print("After adding to the session")

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

print("Hero 2:", hero_2)

print("Hero 3:", hero_3)

session.commit()

print("After committing the session")

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

print("Hero 2:", hero_2)

print("Hero 3:", hero_3)

print("After committing the session, show IDs")

print("Hero 1 ID:", hero_1.id)

print("Hero 2 ID:", hero_2.id)

print("Hero 3 ID:", hero_3.id)

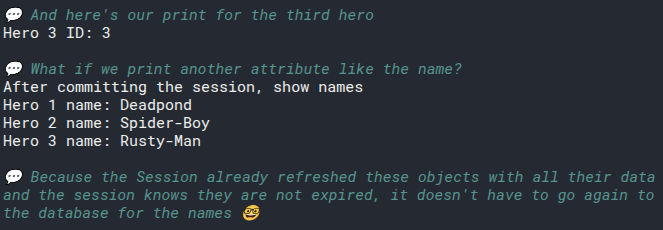

print("After committing the session, show names")

print("Hero 1 name:", hero_1.name)

print("Hero 2 name:", hero_2.name)

print("Hero 3 name:", hero_3.name)

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

Now we are actually accessing the attributes, because instead of printing the whole object hero_1:

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

we are not printing the id attribute in hero.id:

print("Hero 1 ID:", hero_1.id)

By accessing the attribute, that triggers a lot of work done by SQLModel (actually SQLAlchemy) underneath to refresh the data from the database, set it in the object's id attribute, and make it available for the Python expression (in this case just to print it).

Let's see how it works:

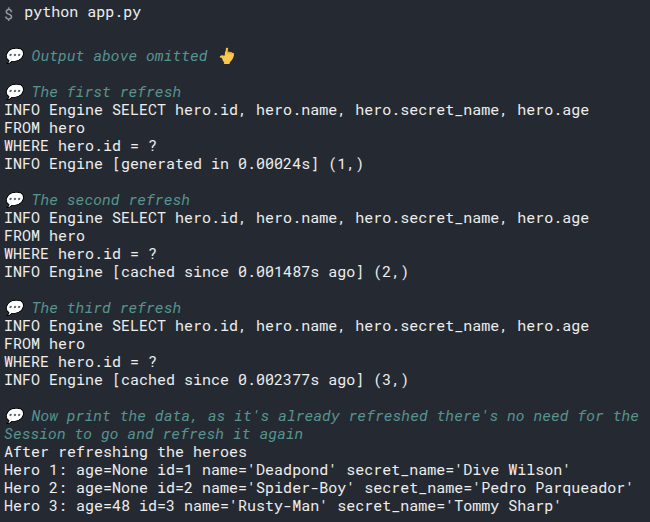

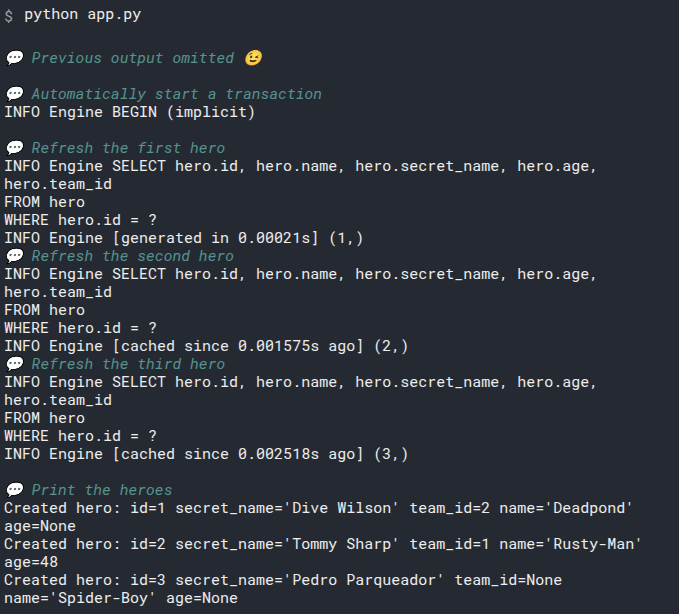

# Refresh Objects Explicitly

You just learnt how the session refreshes the data automatically behind the scenes, as a side effect, when you access an attribute.

But what if you want to explicitly refresh the data?

You can do that too with session.refresh(object):

# Code above omitted

with Session(engine) as session:

session.add(hero_1)

session.add(hero_2)

session.add(hero_3)

print("After adding to the session")

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

print("Hero 2:", hero_2)

print("Hero 3:", hero_3)

session.commit()

print("After committing the session")

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

print("Hero 2:", hero_2)

print("Hero 3:", hero_3)

print("After committing the session, show IDs")

print("Hero 1 ID:", hero_1.id)

print("Hero 2 ID:", hero_2.id)

print("Hero 3 ID:", hero_3.id)

print("After committing the session, show names")

print("Hero 1 name:", hero_1.name)

print("Hero 2 name:", hero_2.name)

print("Hero 3 name:", hero_3.name)

session.refresh(hero_1)

session.refresh(hero_2)

session.refresh(hero_3)

print("After refreshing the heroes")

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

print("Hero 2:", hero_2)

print("Hero 3:", hero_3)

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

When Python executes this code:

session.refresh(hero_1)

When Python executes this code:

session.refresh(hero_1)

the session goes and makes the engine communicate with the database to get the recent data for this object hero_1, and then the session puts the data in the hero_1 object and marks it as "fresh" or "not expired".

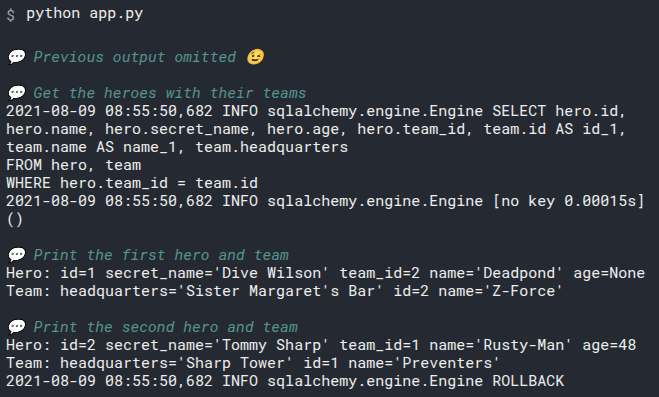

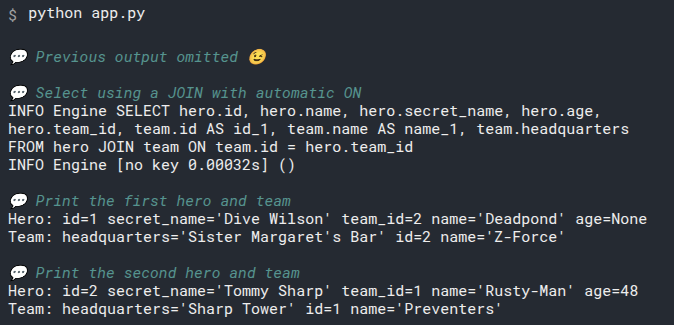

Here's how the output would look like:

This could be useful, for example, if you are building a web API to create heroes. And once a hero is created with some data, you return it to the client.

You wouldn't want to return an object that looks empty because the automatic magic to refresh the data was not triggered.

In this case, after committing the object to the database with the session, you could refresh it, and then return it to the client. This would ensure that the object has its fresh data.

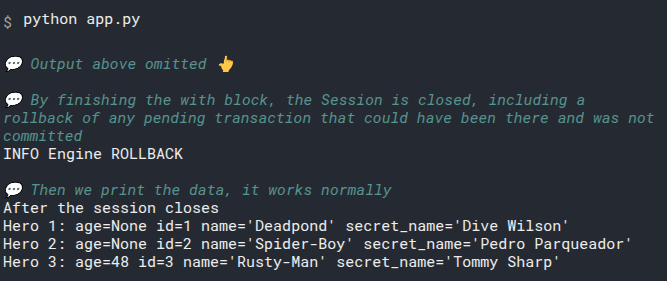

# Print Data After Closing the Session

Now, as a final experiment, we can also print data after the session is closed.

There are no surprises here, it still works:

# Code above omitted

with Session(engine) as session:

session.add(hero_1)

session.add(hero_2)

session.add(hero_3)

print("After adding to the session")

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

print("Hero 2:", hero_2)

print("Hero 3:", hero_3)

session.commit()

print("After committing the session")

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

print("Hero 2:", hero_2)

print("Hero 3:", hero_3)

print("After committing the session, show IDs")

print("Hero 1 ID:", hero_1.id)

print("Hero 2 ID:", hero_2.id)

print("Hero 3 ID:", hero_3.id)

print("After committing the session, show names")

print("Hero 1 name:", hero_1.name)

print("Hero 2 name:", hero_2.name)

print("Hero 3 name:", hero_3.name)

session.refresh(hero_1)

session.refresh(hero_2)

session.refresh(hero_3)

print("After refreshing the heroes")

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

print("Hero 2:", hero_2)

print("Hero 3:", hero_3)

print("After the session closes")

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

print("Hero 2:", hero_2)

print("Hero 3:", hero_3)

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

And the output shows again the same data:

# Review All the Code

Now let's review all this code once again.

from sqlmodel import Field, Session, SQLModel, create_engine

class Hero(SQLModel, table=True):

id: int | None = Field(default=None, primary_key=True)

name: str

secret_name: str

age: int | None = None

sqlite_file_name = "database.db"

sqlite_url = f"sqlite:///{sqlite_file_name}"

engine = create_engine(sqlite_url, echo=True)

def create_db_and_tables():

SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine)

def create_heroes():

hero_1 = Hero(name="Deadpond", secret_name="Dive Wilson")

hero_2 = Hero(name="Spider-Boy", secret_name="Pedro Parqueador")

hero_3 = Hero(name="Rusty-Man", secret_name="Tommy Sharp", age=48)

print("Before interacting with the database")

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

print("Hero 2:", hero_2)

print("Hero 3:", hero_3)

with Session(engine) as session:

session.add(hero_1)

session.add(hero_2)

session.add(hero_3)

print("After adding to the session")

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

print("Hero 2:", hero_2)

print("Hero 3:", hero_3)

session.commit()

print("After committing the session")

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

print("Hero 2:", hero_2)

print("Hero 3:", hero_3)

print("After committing the session, show IDs")

print("Hero 1 ID:", hero_1.id)

print("Hero 2 ID:", hero_2.id)

print("Hero 3 ID:", hero_3.id)

print("After committing the session, show names")

print("Hero 1 name:", hero_1.name)

print("Hero 2 name:", hero_2.name)

print("Hero 3 name:", hero_3.name)

session.refresh(hero_1)

session.refresh(hero_2)

session.refresh(hero_3)

print("After refreshing the heroes")

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

print("Hero 2:", hero_2)

print("Hero 3:", hero_3)

print("After the session closes")

print("Hero 1:", hero_1)

print("Hero 2:", hero_2)

print("Hero 3:", hero_3)

def main():

create_db_and_tables()

create_heroes()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

# Recap

You read all that! That was a lot! Have some cake, you earned it.

We discussed how the session uses the engine to send SQL to the database, to create data and to fetch data too. How it keeps track of "expired" and "fresh" data. At which moments it fetches data automatically (when accessing instance attributes) and how that data is synchronized between objects in memory and the database via the session.

If you understood all that, now you know a lot about SQLModel, SQLAlchemy, and how the interactions from Python with databases work in general.

If you didn't get all that, it's fine, you can always come back later to refresh the concepts.

# Read Data - SELECT

We already have a database and a table with some data in it that looks more or less like this:

| id | name | secret_name | age |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Deadpond | Dive Wilson | null |

| 2 | Spider-Boy | Pedro Parqueador | null |

| 3 | Rusty-Man | Tommy Sharp | 48 |

Things are getting more exciting! Let's now see how to read data from the database!

# Continue From Previous Code

Let's continue from the last code we used to create some data.

from sqlmodel import Field, Session, SQLModel, create_engine

class Hero(SQLModel, table=True):

id: int | None = Field(default=None, primary_key=True)

name: str

secret_name: str

age: int | None = None

sqlite_file_name = "database.db"

sqlite_url = f"sqlite:///{sqlite_file_name}"

engine = create_engine(sqlite_url, echo=True)

def create_db_and_tables():

SQLModel.metadata.create_all(engine)

def create_heroes():

hero_1 = Hero(name="Deadpond", secret_name="Dive Wilson")

hero_2 = Hero(name="Spider-Boy", secret_name="Pedro Parqueador")

hero_3 = Hero(name="Rusty-Man", secret_name="Tommy Sharp", age=48)

with Session(engine) as session:

session.add(hero_1)

session.add(hero_2)

session.add(hero_3)

session.commit()

def main():

create_db_and_tables()

create_heroes()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

We are creating a SQLModel Hero class model and creating some records.

We will need the Hero model and the engine, but we will create a new session to query data in a new function.

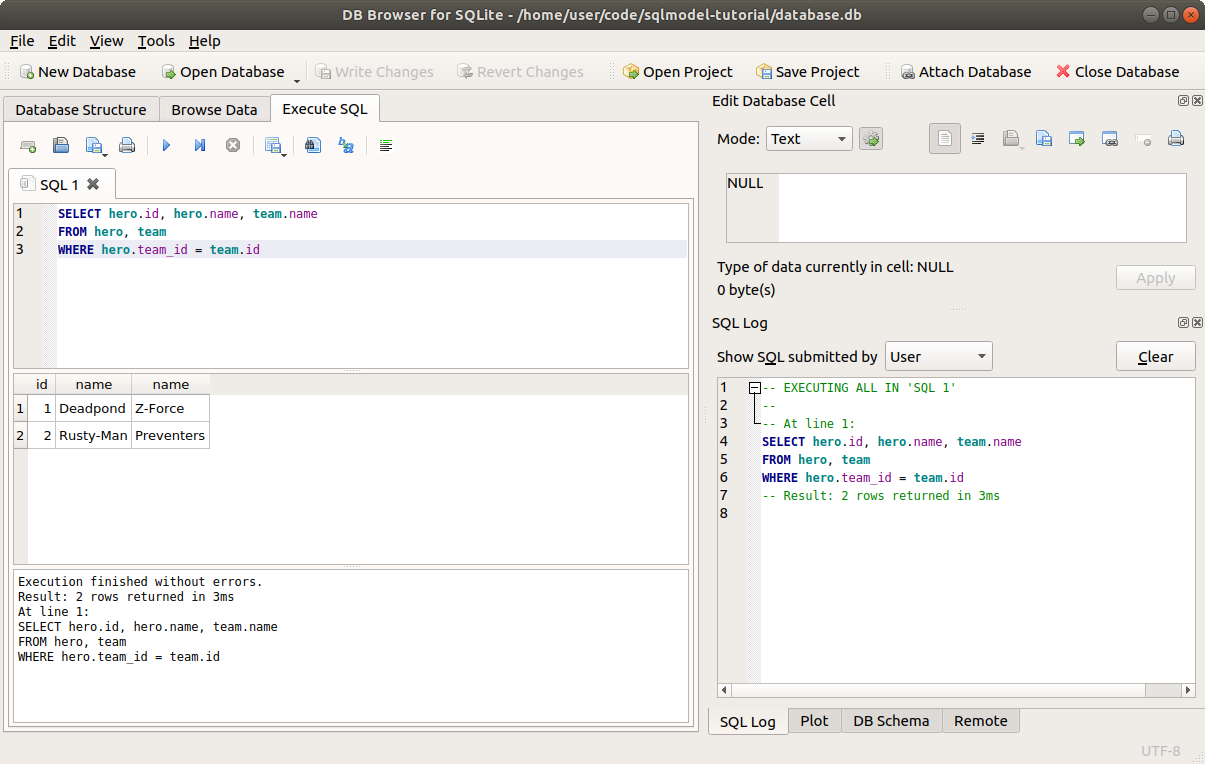

# Read Data with SQL

Before writing Python code let's do a quick review of how querying data with SQL looks like:

SELECT id, name, secret_name, age

FROM hero

2

Then the database will go and get the data and return it to you in a table like this:

| id | name | secret_name | age |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Deadpond | Dive Wilson | null |

| 2 | Spider-Boy | Pedro Parqueador | null |

| 3 | Rusty-Man | Tommy Sharp | 48 |

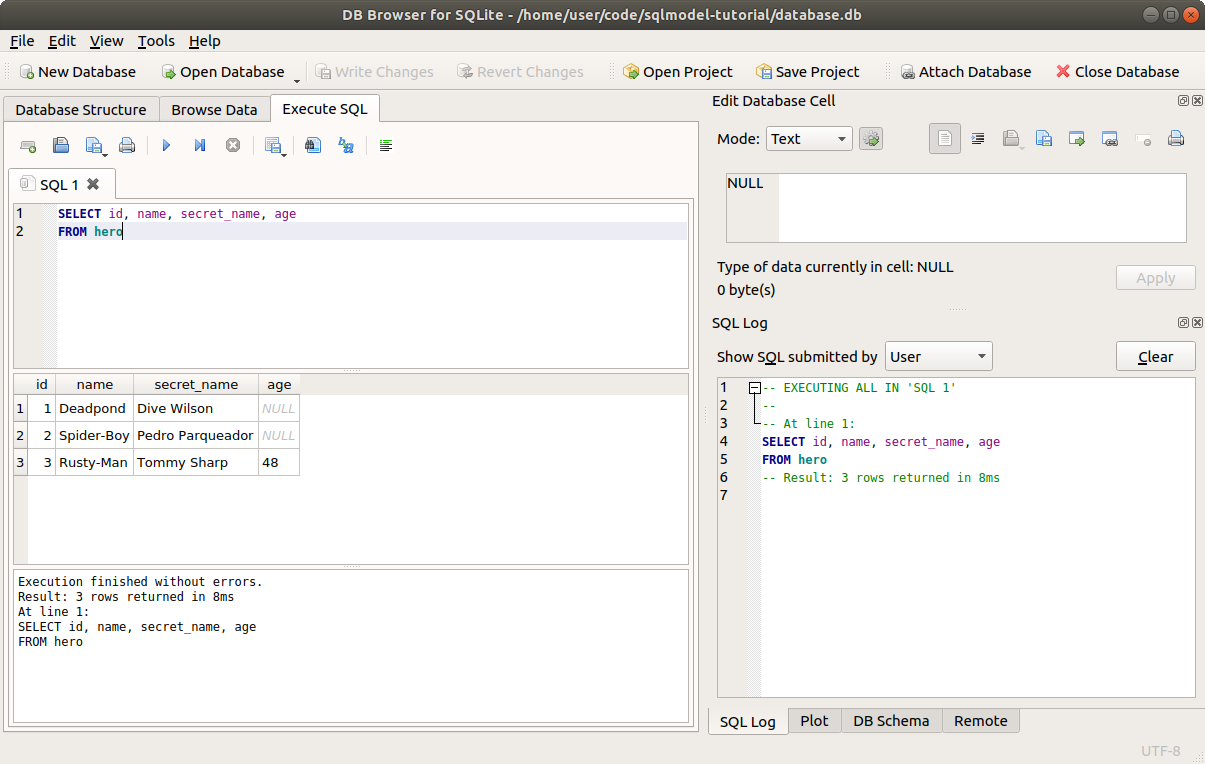

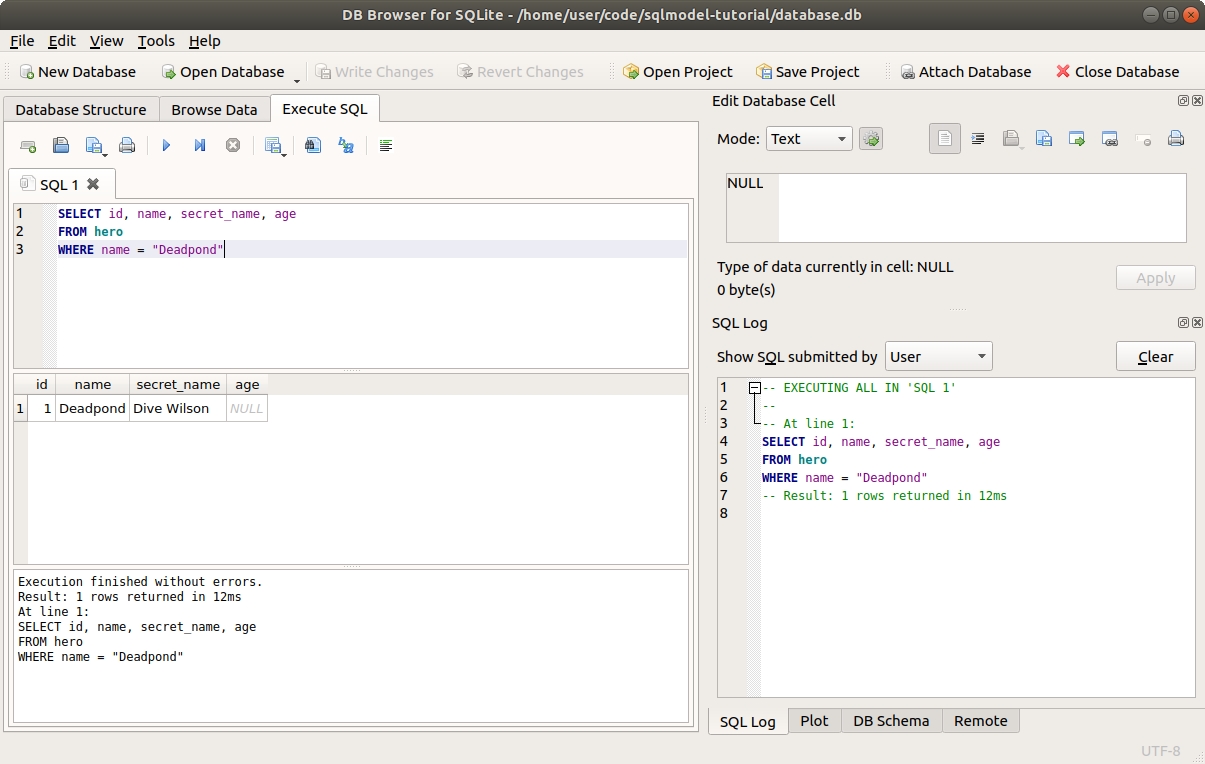

You can try that out in DB Browser for SQLite:

Here we are getting all the rows.

If you have thousands of rows, that could be expensive to compute for the database.

You would normally want to filter the rows to receive only the ones you want. But we'll learn about that later in the next chapter.

# A SQL Shortcut

If we want to get all the columns like in this case above, in SQL there's a shortcut, instead of specifying each of the column names we could write a *:

SELECT * FROM hero;

That would end up in the same result. Although we won't use that for SQLModel.

# SELECT Fewer Columns

We can also SELECT fewer columns, for example:

SELECT id, name FROM hero;

Here we are only selecting the id and name columns.

And it would result in a table like this:

| id | name |

|---|---|

| 1 | Deadpond |

| 2 | Spider-Boy |

| 3 | Rusty-Man |

And here is something interesting to notice. SQL databases store their data in tables. And they also always communicate their results in tables.

# SELECT Variants

The SQL language allows serveral variations in serveral places.

One of those variations is that in SELECT statements you can use the names of the columns directly, or you can prefix them with the name of the table and a dot.

For example, the same SQL code above could be written as:

SELECT hero.id, hero.name, hero.secret_name, hero.age FROM hero;

This will be particularly imortant later when working with multiple tables at the same time that could have the same name for some columns.

For example hero.id and team.id, or hero.name and team.name.

Another variation is that most of the SQL keywords like SELECT can also be written in lowercase, like select.

# Result Tables Don't Have to Exist

This is the interesting part. The tables returned by SQL databases don't have to exist in the database as independent tables.

For example, in our database, we only have one table that has all the columns, id, name, secret_name, age. And here we are getting a result table with fewer columns.

One of the main points of SQL is to be able to keep the data structured in different tables, without repeating data, etc, and then query the database in many ways and get many different tables as a result.

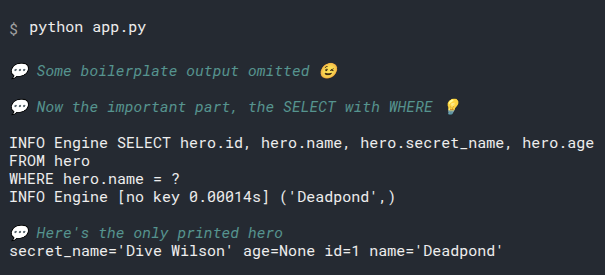

# Read Data with SQLModel

Now let's do the same query to read all the heroes, but with SQLModel.

# Create a Session

The first step is to create a Session, the same way we did when creating the rows.

We will start with that in a new function select_heroes():

# Code above omitted

def select_heroes():

with Session(engine) as session:

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

# Create a select Statement

Next, pretty much the same way we wrote a SQL SELECT statement above, now we'll create a SQLModel select statement.

First we have to import select from sqlmodel at the top of the file:

from sqlmodel import Field, Session, SQLModel, create_engine, select

# Code below omitted

2

3

And then we will use it to create a SELECT statement in Python code:

from sqlmodel import Field, Session, SQLModel, create_engine, select

# Code here omitted

def select_heroes():

with Session(engine) as session:

statement = select(Hero)

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

It's a very simple line of code that conveys a lot of information:

statement = select(Hero)

This is equivalent to the first SQL SELECT statement above:

SELECT id, name, secret_name, age FROM hero;

We pass the class model Hero to the select() function. And that tells it that we want to select all the columns necessary for the Hero class.

And notice that in the select() function we don't explicitly specify the FROM part. It is already abvious to SQLModel (actually to SQLAlchemy) that we want to select FROM the table hero, because that's the one associated with the Hero class model.

The value of the statement returned by select() is a special object that allows us to do other things. I'll tell you about that in the next chapters.

# Execute the Statement

Now that we have the select statement, we can execute it with the session:

# Code above omitted

def select_heroes():

with Session(engine) as session:

statement = select(Hero)

results = session.exec(statement)

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

This will tell the session to go ahead and use the engine to execute that SELECT statement in the database and bring the results back.

Because we created the engine with echo=True, it will show the SQL it executes in the output.

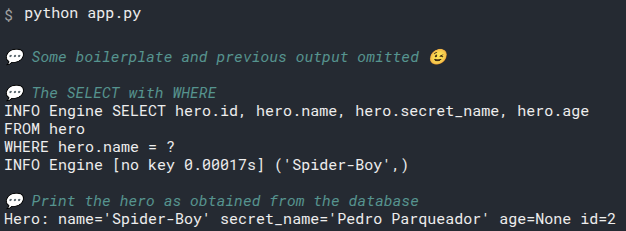

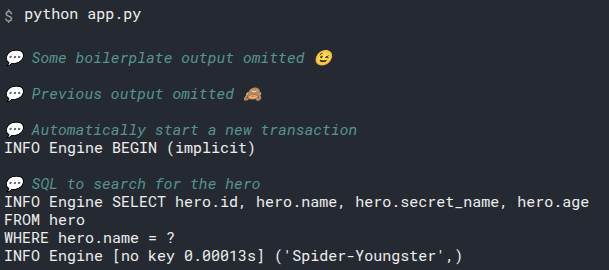

This session.exec(statement) will generate this output:

INFO Engine BEGIN (implicit)

INFO Engine SELECT hero.id, hero.name, hero.secret_name, hero.age

FROM hero

INFO Engine [no key 0.00032s] ()

2

3

4

The database returns the table with all the data, just like above when we wrote SQL directly.

# Iterate Through the Results

The results object is an iterable that can be used to go through each one of the rows.

Now we can put it in a for loop and print each one of the heroes:

# Code above omitted

def select_heroes():

with Session(engine) as session:

statement = select(Hero)

results = session.exec(statement)

for hero in results:

print(hero)

# Code below omitted

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

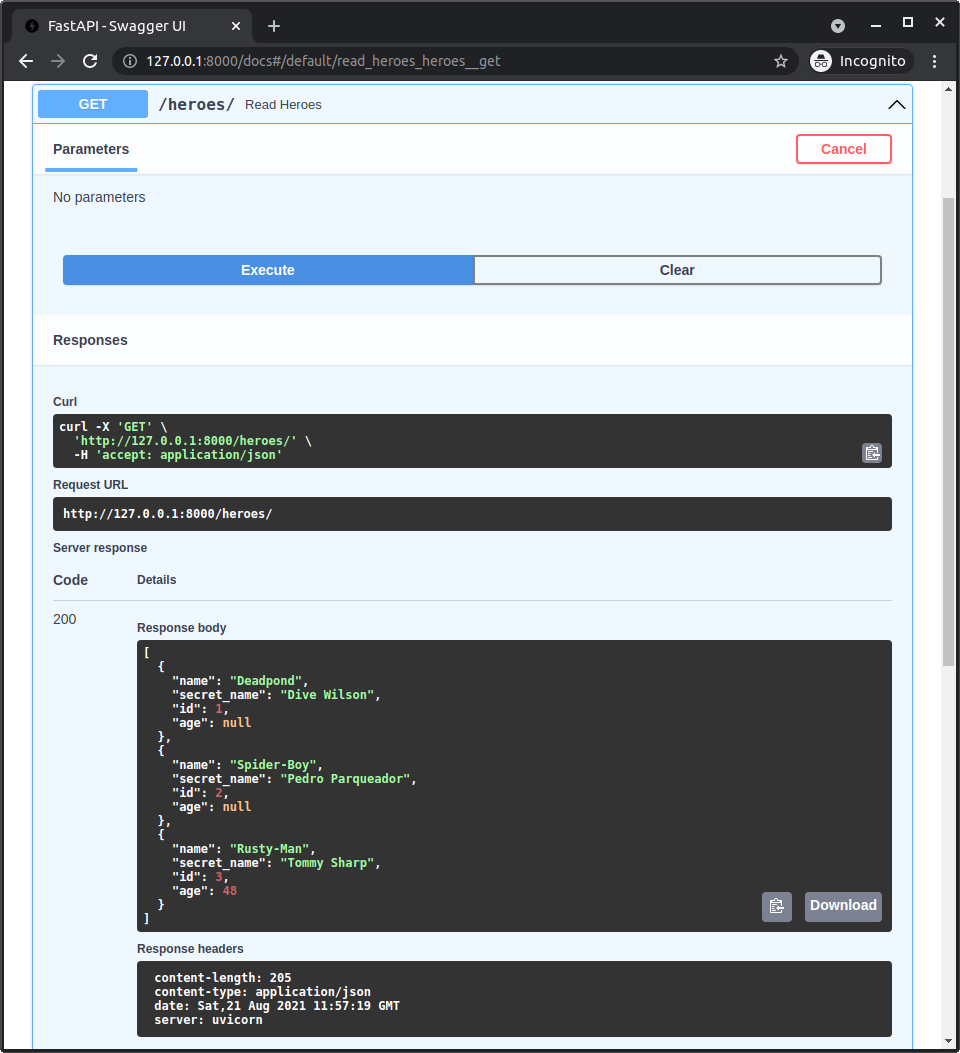

This will print the output:

id=1 name='Deadpond' age=None secret_name='Dive Wilson'

id=2 name='Spider-Boy' age=None secret_name='Pedro Parqueador'

id=3 name='Rusty-Man' age=48 secret_name='Tommy Sharp'

2

3

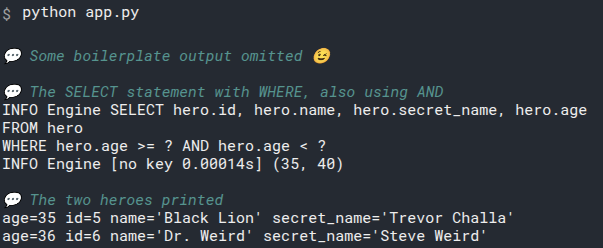

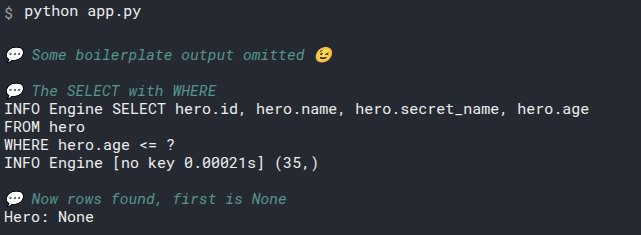

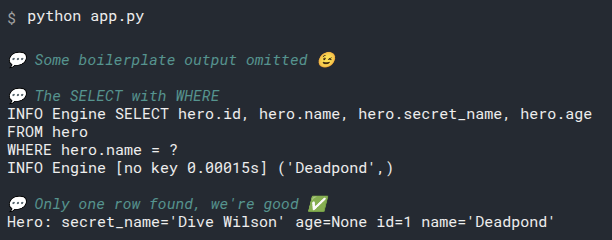

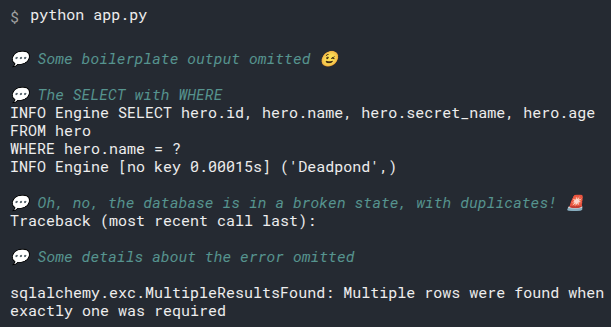

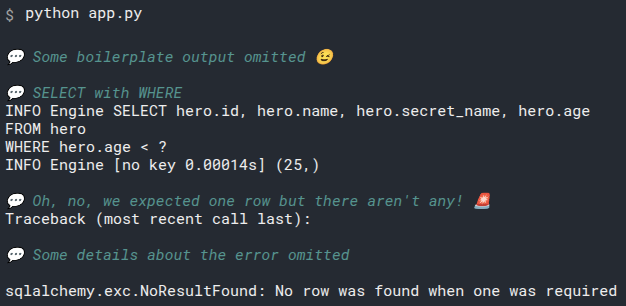

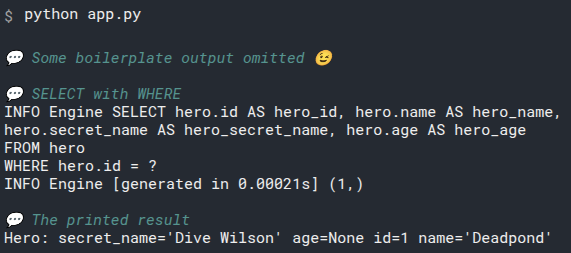

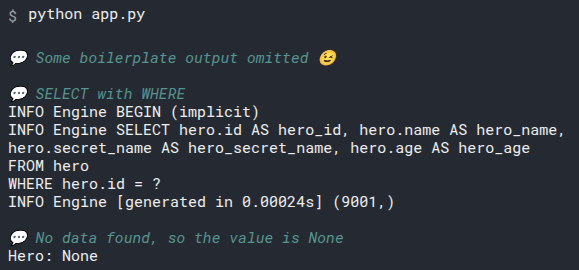

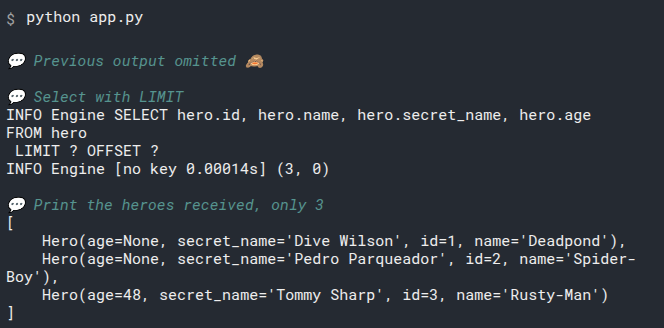

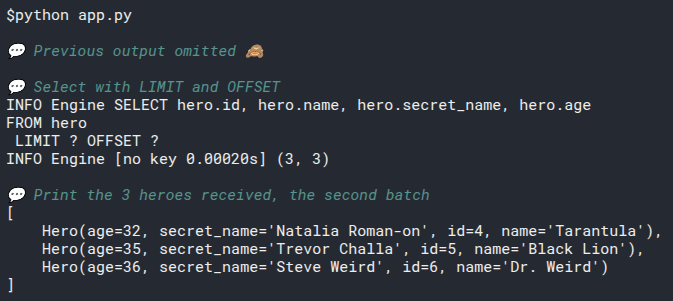

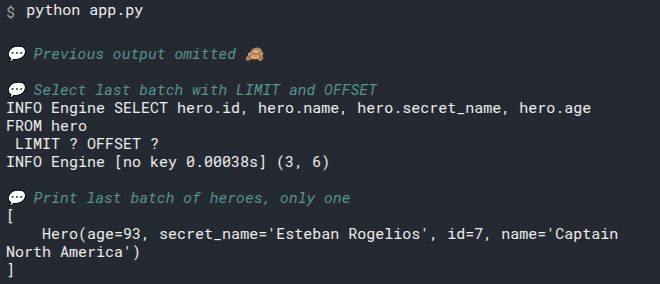

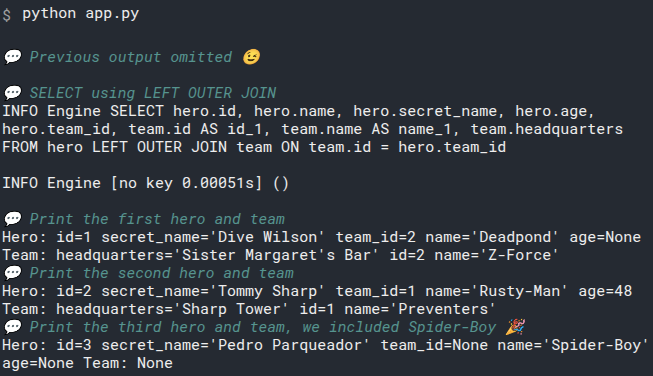

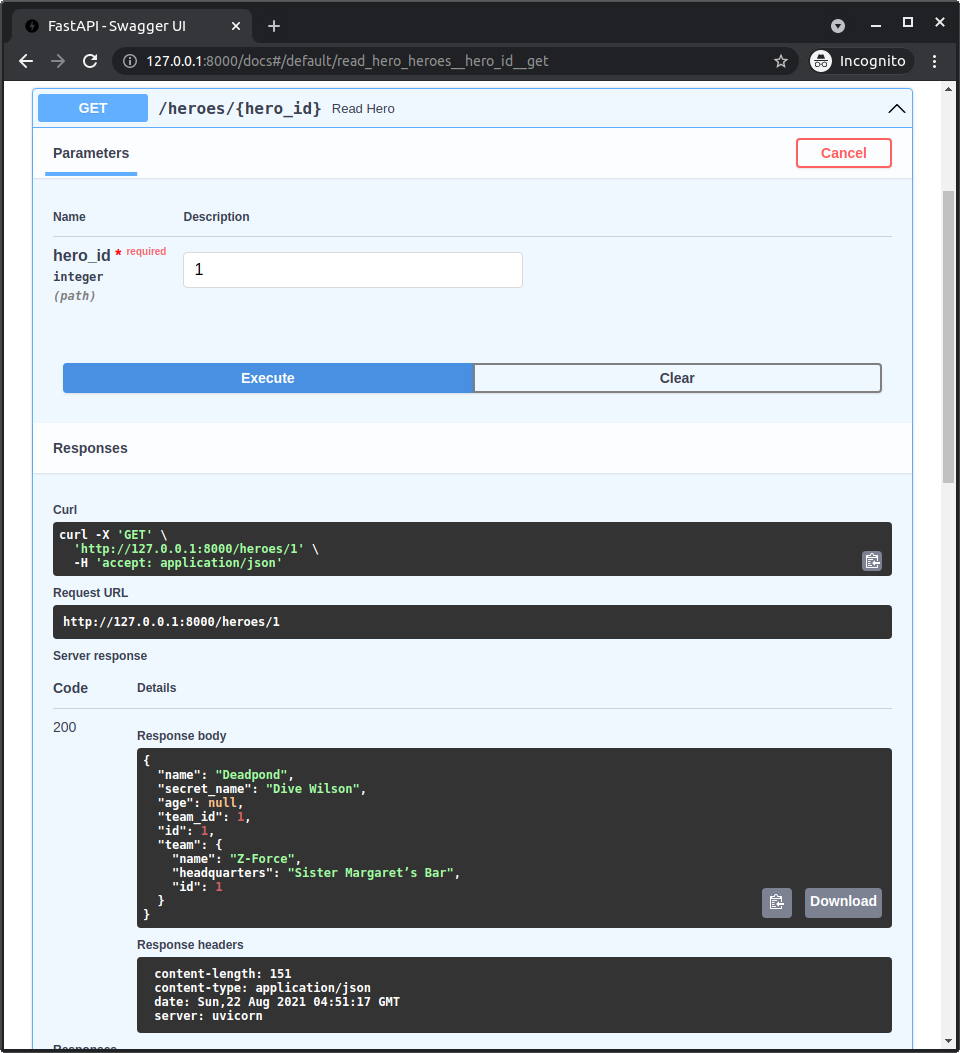

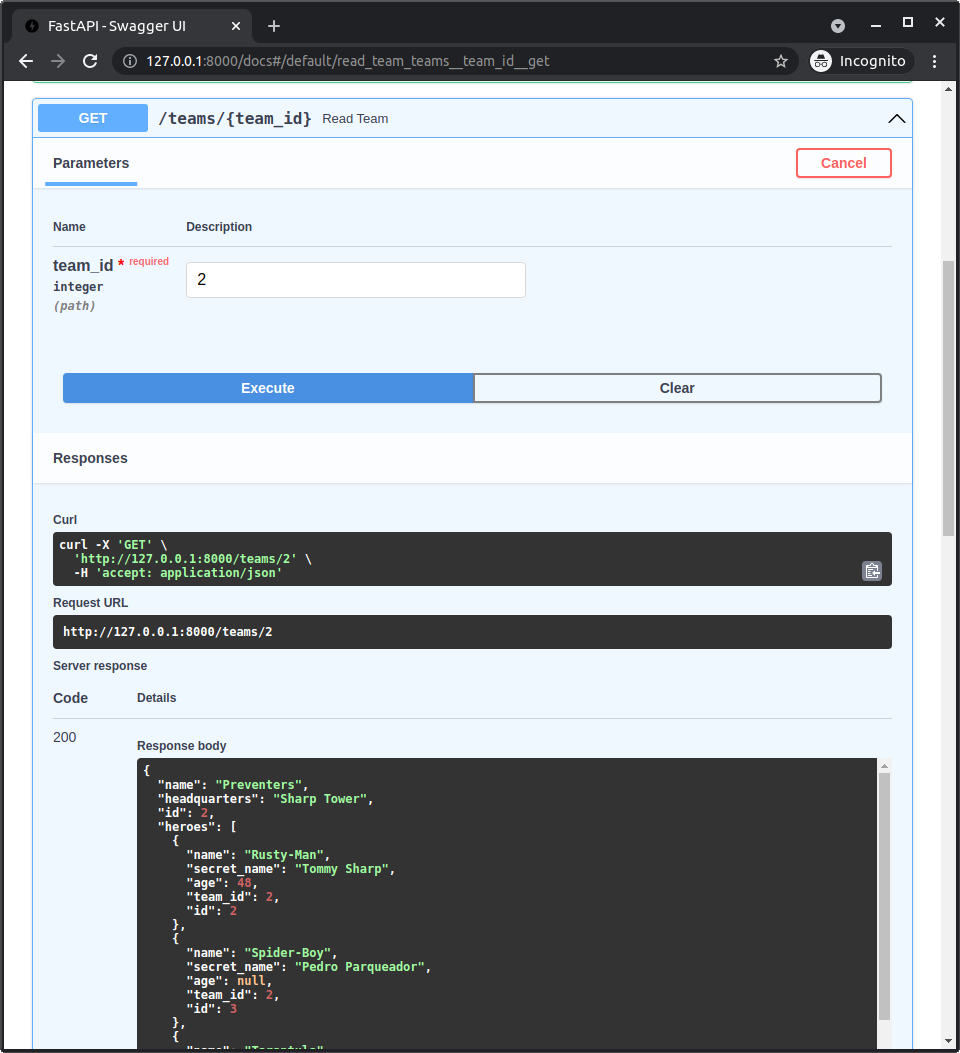

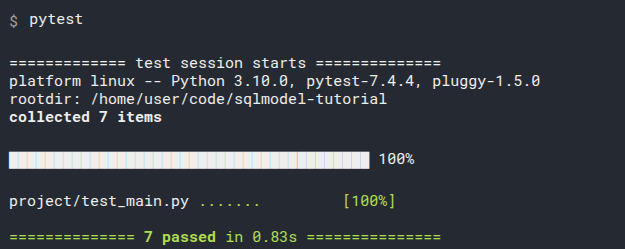

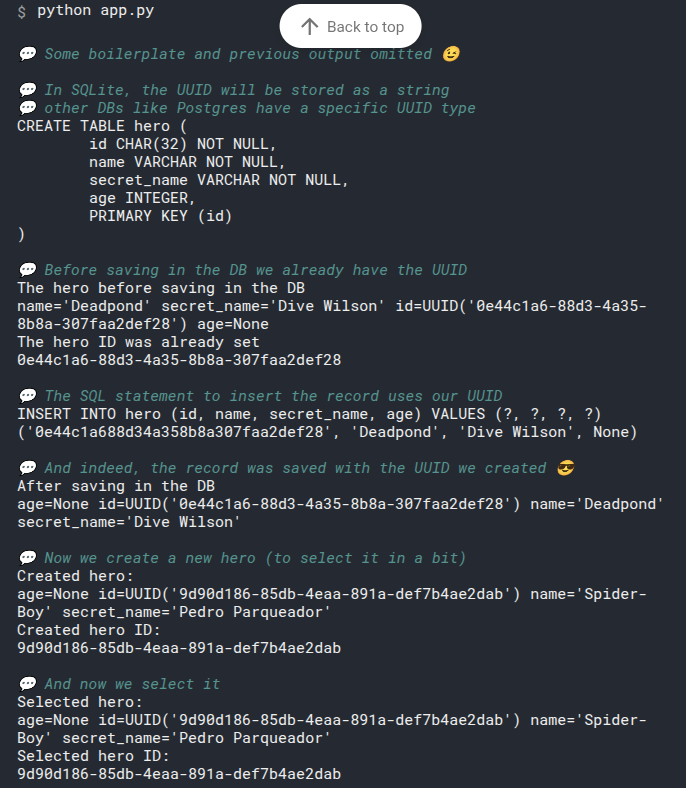

# Add select_heroes() to main()